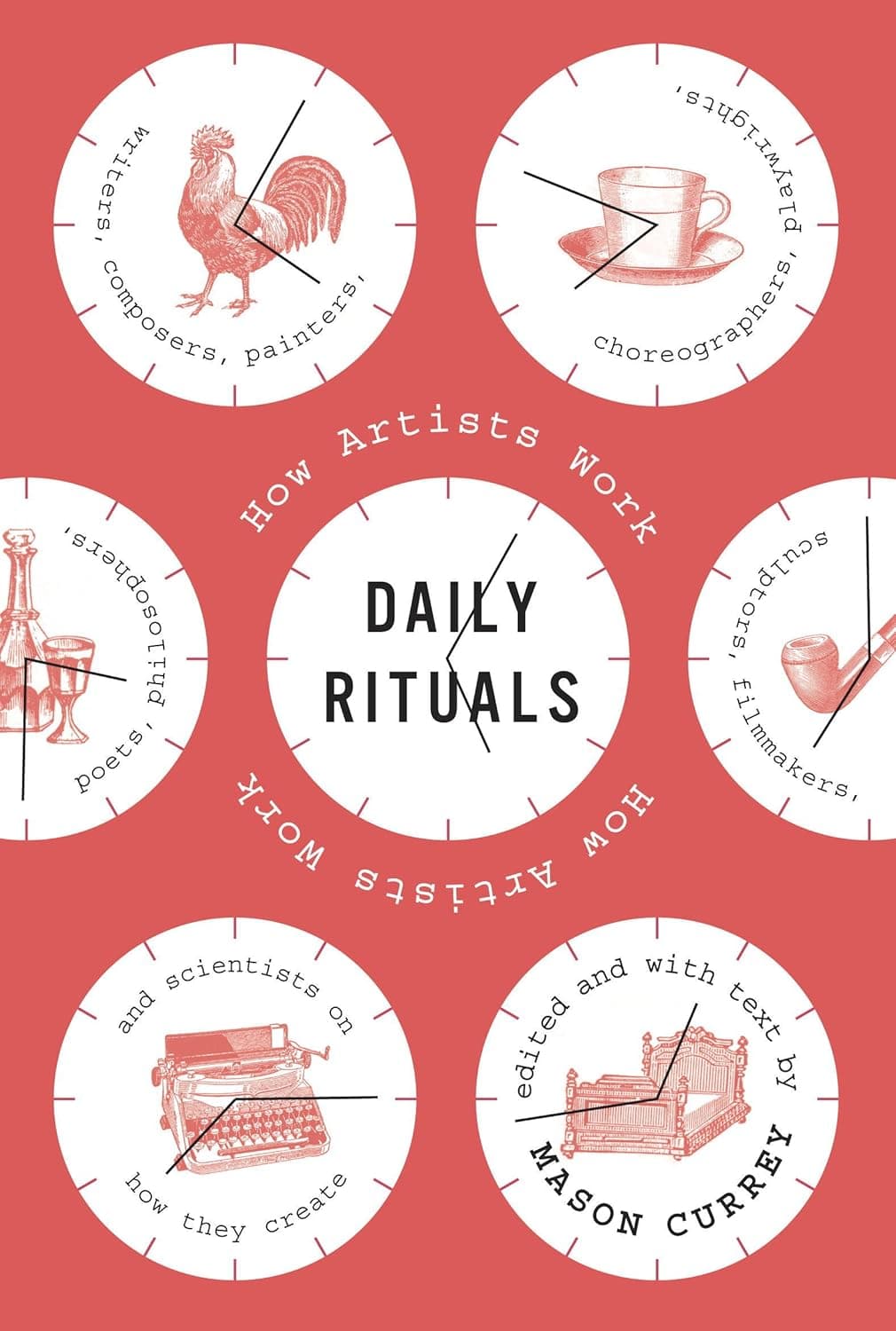

Daily Rituals

By: Mason Currey

Category: Productivity

Finished:

Highlights

A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods.

This was one of William James’s favorite subjects. He thought you wanted to put part of your life on autopilot; by forming good habits, he said, we can “free our minds to advance to really interesting fields of action.” Ironically, James himself was a chronic procrastinator and could never stick to a regular schedule

“Sooner or later,” Pritchett writes, “the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.”

W.H. Auden

“A modern stoic,” he observed, “knows that the surest way to discipline passion is to discipline time: decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.”

To maintain his energy and concentration, the poet relied on amphetamines, taking a dose of Benzedrine each morning the way many people take a daily multivitamin. At night, he used Seconal or another sedative to get to sleep.

Auden regarded amphetamines as one of the “labor-saving devices” in the “mental kitchen,” alongside alcohol, coffee, and tobacco

Francis Bacon

when he wasn’t painting, Bacon lived a life of hedonistic excess, eating multiple rich meals a day, drinking tremendous quantities of alcohol, taking whatever stimulants were handy, and generally staying out later and partying harder than any of his contemporaries.

Bacon depended on pills to get to sleep, and he would read and reread classic cookbooks to relax himself before bed.

Even the occasional hangover was, in Bacon’s mind, a boon. “I often like working with a hangover,” he said, “because my mind is crackling with energy and I can think very clearly.”

Simone de Beauvoir

Beauvoir rarely had difficulty working; if anything, the opposite was true—when she took her annual two- or three-month vacations, she found herself growing bored and uncomfortable after a few weeks away from her work.

Thomas Wolfe

Wolfe tried to figure out what had prompted the sudden change—and realized that, at the window, he had been unconsciously fondling his genitals, a habit from childhood that, while not exactly sexual (his “penis remained limp and unaroused,” he noted in a letter to his editor), fostered such a “good male feeling” that it had stoked his creative energies. From then on, Wolfe regularly used this method to inspire his writing sessions, dreamily exploring his “male configurations” until “the sensuous elements in every domain of life became more immediate, real, and beautiful.”

Morton Feldman

“He said that it’s a very good idea that after you write a little bit, stop and then copy it. Because while you’re copying it, you’re thinking about it, and it’s giving you other ideas. And that’s the way I work. And it’s marvelous, just wonderful, the relationship between working and copying.”

Beethoven

His breakfast was coffee, which he prepared himself with great care—he determined that there should be sixty beans per cup, and he often counted them out one by one for a precise dose.

Kierkegaard

before coffee could be served, Levin had to select which cup and saucer he preferred that day, and then, bizarrely, justify his choice to Kierkegaard.

Ben Franklin

In his Autobiography, Franklin famously outlined a scheme to achieve “moral perfection” according to a thirteen-week plan. Each week was devoted to a particular virtue—temperance, cleanliness, moderation, et cetera—and his offenses against these virtues were tracked on a calendar. Franklin thought that if he could maintain his devotion to one virtue for an entire week, it would become a habit; then he could move on to the next virtue, successively making fewer and fewer offenses

Anthony Trollope

All those I think who have lived as literary men,—working daily as literary labourers,—will agree with me that three hours a day will produce as much as a man ought to write. But then, he should so have trained himself that he shall be able to work continuously during those three hours,—so have tutored his mind that it shall not be necessary for him to sit nibbling his pen, and gazing at the wall before him, till he shall have found the words with which he wants to express his ideas.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Toulouse-Lautrec did his best creative work at night, sketching at cabarets or setting up his easel in brothels. The resulting depictions of fin de siècle Parisian nightlife made his name, but the cabaret lifestyle proved disastrous to his health: Toulouse-Lautrec drank constantly and slept little.

Karl Marx

Marx relied on his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels to send him regular handouts, which Engels pilfered from the petty-cash box of his father’s textile firm—and which Marx promptly misspent, having no money-management skills whatsoever.

his boils would get so bad that he “could neither sit nor walk nor remain upright,”

Gertrude Stein

Stein confirmed that she had never been able to write much more than half an hour a day—but added, “If you write a half hour a day it makes a lot of writing year by year. To be sure all day and every day you are waiting around to write that half hour a day.”

Ernest Hemingway

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again.

He wrote standing up, facing a chest-high bookshelf with a typewriter on top, and on top of that a wooden reading board.

Henry Miller

Two or three hours in the morning were enough for him, although he stressed the importance of keeping regular hours in order to cultivate a daily creative rhythm. “I know that to sustain these true moments of insight one has to be highly disciplined, lead a disciplined life,” he said.

William Faulkner

“I write when the spirit moves me,” Faulkner said, “and the spirit moves me every day.”

Ann Beattie

“The times that I’ve tried that, when I have been in a slump and I try to get out of it by saying, ‘Come on, Ann, sit down at that typewriter,’ I’ve gotten in a worse slump. It’s better if I just let it ride.” As a result, she often won’t write anything for months.

Haruki Murakami

Murakami wakes at 4:00 A.M. and works for five to six hours straight. In the afternoons he runs or swims (or does both), runs errands, reads, and listens to music; bedtime is 9:00. “I keep to this routine every day without variation,” he told The Paris Review in 2004. “The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.”

Joyce Carol Oates

the first several weeks of a new novel, Oates has said, are particularly difficult and demoralizing: “Getting the first draft finished is like pushing a peanut with your nose across a very dirty floor.”

Chuck Close

“In an ideal world, I would work six hours a day, three hours in the morning and three hours in the afternoon,” Close said

“Inspiration is for amateurs,” Close says. “The rest of us just show up and get to work.”

John Adams

“My experience has been that most really serious creative people I know have very, very routine and not particularly glamorous work habits,”

B.F. Skinner

The founder of behavioral psychology treated his daily writing sessions much like a laboratory experiment, conditioning himself to write every morning with a pair of self-reinforcing behaviors: he started and stopped by the buzz of a timer, and he carefully plotted the number of hours he wrote and the words he produced on a graph.

Jonathan Edwards

For the horseback rides, he employed a mnemonic device, described by the biographer George W. Marsden: “For each insight he wished to remember, he would pin a small piece of paper on a particular part of his clothes, which he would associate with the thought. When he returned home he would unpin these and write down each idea. At the ends of trips of several days, his clothes might be covered by quite a few of these slips of paper.”

William James

The more of the details of our daily life we can hand over to the effortless custody of automatism, the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for their own proper work. There is no more miserable human being than one in whom nothing is habitual but indecision, and for whom the lighting of every cigar, the drinking of every cup, the time of rising and going to bed every day, and the beginning of every bit of work, are subjects of express volitional deliberation.

James was writing from personal experience—the hypothetical sufferer is, in fact, a thinly disguised description of himself. For James kept no regular schedule, was chronically indecisive, and lived a disorderly, unsettled life.

Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky worked on his compositions daily, with or without inspiration, he said. He required solitude for the task, and always closed the windows of his studio before he began: “I have never been able to compose unless sure that no one could hear me.” If he felt blocked, the composer might execute a brief headstand, which, he said, “rests the head and clears the brain.”

Picasso

Picasso took over its large, airy studio, forbade anyone from entering without his permission, and surrounded himself with his painting supplies, piles of miscellaneous junk, and a menagerie of pets, including a dog, three Siamese cats, and a monkey named Monina.

Painting, on the other hand, never bored or tired him. Picasso claimed that, even after three or four hours standing in front of a canvas, he did not feel the slightest fatigue. “That’s why painters live so long,” he said. “While I work I leave my body outside the door, the way Moslems take off their shoes before entering the mosque.”

Sartre

“One can be very fertile without having to work too much,” Sartre once said. “Three hours in the morning, three hours in the evening. This is my only rule.”

By the 1950s, too much work on too little sleep—with too much wine and cigarettes—had left Sartre exhausted and on the verge of collapse. Rather than slow down, however, he turned to Corydrane, a mix of amphetamine and aspirin then fashionable among Parisian students, intellectuals, and artists (and legal in France until 1971, when it was declared toxic and taken off the market). The prescribed dose was one or two tablets in the morning and at noon. Sartre took twenty a day, beginning with his morning coffee and slowly chewing one pill after another as he worked.

“His diet over a period of twenty-four hours included two packs of cigarettes and several pipes stuffed with black tobacco, more than a quart of alcohol—wine, beer, vodka, whisky, and so on—two hundred milligrams of amphetamines, fifteen grams of aspirin, several grams of barbiturates, plus coffee, tea, rich meals.”

Sylvia Plath

She was using sedatives to get to sleep, and when they wore off at about 5:00 A.M. she would get up and write until the children awoke. Working like this for two months in the autumn of 1962, she produced nearly all the poems of Ariel, the posthumously published collection that finally established her as a major and searingly original new voice in poetry.

Louis Armstrong

Armstrong never ate dinner before a show, but he would sometimes go out for a late supper afterward or, more often, retreat to his hotel room for a room-service meal or take-out Chinese food, his second-favorite cuisine (after red beans and rice). Then he would roll a joint—Armstrong openly smoked pot, or “gage,” as he called it, nearly every day, believing it to be far superior to alcohol—catch up on his voluminous correspondence, and listen to music on the two reel-to-reel tape recorders that followed him wherever he went.

Woody Allen

I’ve found over the years that any momentary change stimulates a fresh burst of mental energy. So if I’m in this room and then I go into the other room, it helps me. If I go outside to the street, it’s a huge help. If I go up and take a shower it’s a big help. So I sometimes take extra showers. I’ll be down here [in the living room] and at an impasse and what will help me is to go upstairs and take a shower. It breaks up everything and relaxes me.

David Lynch

For seven years I ate at Bob’s Big Boy. I would go at 2:30, after the lunch rush. I ate a chocolate shake and four, five, six, seven cups of coffee—with lots of sugar. And there’s lots of sugar in that chocolate shake. It’s a thick shake. In a silver goblet. I would get a rush from all this sugar, and I would get so many ideas! I would write them on these napkins. It was like I had a desk with paper. All I had to do was remember to bring my pen, but a waitress would give me one if I remembered to return it at the end of my stay. I got a lot of ideas at Bob’s.

Maya Angelou

Angelou has never been able to write at home. “I try to keep home very pretty,” she has said, “and I can’t work in a pretty surrounding. It throws me.”

Truman Capote

Writing in bed was the least of Capote’s superstitions. He couldn’t allow three cigarette butts in the same ashtray at once, and if he was a guest at someone’s house, he would stuff the butts in his pocket rather than overfill the tray.

Frank Lloyd Wright

(For Falling-water, perhaps the most famous residence of the twentieth century, Wright didn’t begin the drawings until the client called to say he was getting in the car and would be arriving for their meeting in a little more than two hours.)

Tesla

Tesla worked best in the dark and would raise the blinds again only in the event of a lightning storm, which he liked to watch flashing above the cityscape from his black mohair sofa.

Upon arriving, he was shown to his regular table, where eighteen clean linen napkins would be stacked at his place. As he waited for his meal, he would polish the already gleaming silver and crystal with these squares of linen, gradually amassing a heap of discarded napkins on the table. And when his dishes arrived—served to him not by a waiter but by the maître d’hôtel himself—Tesla would mentally calculate their cubic contents before eating, a strange compulsion he had developed in his childhood and without which he could never enjoy his food.

John Milton

Milton was totally blind for the last twenty years of his life, yet he managed to produce a steady stream of writing, including his magnum opus, the ten-thousand-line epic poem Paradise Lost, composed between 1658 and 1664.

Descartes

Arriving in Sweden, in time for one of the coldest winters in memory, Descartes was notified that his lessons to Queen Christina would take place in the mornings—beginning at 5:00 A.M. He had no choice but to obey. But the early hours and bitter cold were too much for him. After only a month on the new schedule, Descartes fell ill, apparently of pneumonia; ten days later he was dead.

Goethe

These moods were the bane of Goethe’s later existence; he thought it futile to try to work without the spark of inspiration. He said, “My advice therefore is that one should not force anything; it is better to fritter away one’s unproductive days and hours, or sleep through them, than to try at such times to write something which will give one no satisfaction later on.”

Victor Hugo

When Napoléon III seized control of France in 1851, Hugo was forced into political exile, eventually settling with his family on Guernsey, a British island off the coast of Normandy. In his fifteen years there Hugo would write some of his best work, including three collections of poetry and the novel Les Misérables.

Chief among them was an all-glass “lookout” on the roof that resembled a small, furnished greenhouse. This was the highest point on the island, with a panoramic view of the English Channel; on clear days, you could see the coast of France. There Hugo wrote each morning, standing at a small desk in front of a mirror.

After reading the passionate words of “Juju” to her “beloved Christ,” Hugo swallowed two raw eggs, enclosed himself in his lookout, and wrote until 11:00 A.M. Then he stepped out onto the rooftop and washed from a tub of water left out overnight, pouring the icy liquid over himself and rubbing his body with a horsehair glove. Townspeople passing by could watch the spectacle from the street—as could Juliette, looking out the window of her room.

At noon Hugo headed downstairs for lunch. The biographer Graham Robb writes, “these were the days when prominent men were expected to have opening hours like museums.

Charles Dickens

First, he needed absolute quiet; at one of his houses, an extra door had to be installed to his study to block out noise. And his study had to be precisely arranged, with his writing desk placed in front of a window and, on the desk itself, his writing materials—goose-quill pens and blue ink—laid out alongside several ornaments: a small vase of fresh flowers, a large paper knife, a gilt leaf with a rabbit perched upon it, and two bronze statuettes (one depicting a pair of fat toads dueling, the other a gentleman swarmed with puppies).

Buckminster Fuller

After trying many schemes, Bucky found a schedule that worked for him: He catnapped for approximately thirty minutes after each six hours of work; sooner if signaled by what he called “broken fixation of interest.” It worked (for him). I can personally attest that many of his younger colleagues and students could not keep up with him.

Nevertheless, despite the apparent success of his high-frequency-sleep experiment, Fuller did not stick with it indefinitely; eventually his wife complained of his odd hours, and Bucky went back to a more normal schedule, although he continued to take catnaps during the day as needed.

Paul Erdos

After the bet, Erdos promptly resumed his amphetamine habit, which he supplemented with shots of strong espresso and caffeine tablets. “A mathematician,” he liked to say, “is a machine for turning coffee into theorems.”

John Updike

But I’ve never been a night writer, unlike some of my colleagues, and I’ve never believed that one should wait until one is inspired because I think that the pleasures of not writing are so great that if you ever start indulging them you will never write again. So, I try to be a regular sort of fellow—much like a dentist drilling his teeth every morning—except Sunday, I don’t work on Sunday, and there are of course some holidays I take.

Ayn Rand

According to the biographer Anne C. Heller, Rand had spent years planning and composing the first third of her novel; over the next twelve months, fueled by Benzedrine pills, she averaged a chapter a week.

The Benzedrine helped Rand push through the last stages of The Fountainhead, but it soon became a crutch. She would continue to use amphetamines for the next three decades, even as her overuse led to mood swings, irritability, emotional outbursts, and paranoia—traits Rand was susceptible to even without drugs.

Twyla Tharp

I begin each day of my life with a ritual: I wake up at 5:30 A.M., put on my workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweatshirts, and my hat. I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go I have completed the ritual.