The 4-Hour Chef

By: Tim Ferriss

Categories: Learning, Productivity

Finished:

Highlights

Averages are bad indicators because in extremistan / non-linear situations (see Antifragile) you get major outliers that destroy the average (Bill Gates walks into a bar, the average net worth goes up by a billion dollars).

What you study is frequently more important than how you study. You can spend a lot of time studying things you don’t need (learning “niece” in Spanish when you have no nieces).

Two lenses for viewing learning methods:

- Is the method effective? Have you narrowed down your material to the highest frequency?

- Is the method sustainable? Have you chosen a schedule and subject matter that you can stick with (or at least put up with) until reaching fluency? Will you actually swallow the pill you’ve prescribed yourself?

Use “DiSSS” and “CaFE” as frameworks for learning:

DiSSS

- Deconstruction: What are the minimal learning units, the lego blocks, that you should be starting with?

- Selection: Which 20% of the lego blocks will give me 80% of the results?

- Sequencing: In what order should I learn the blocks?

- Stakes: How can I create real stakes to make sure I follow through on the program I’ve prescribed myself?

CaFE

- Compression: Can I compress the most important 20% into an easy to grasp 1 pager

- Frequency: How frequently should I practice? Can I cram? What walls will I hit? What’s the minimum effective dose for volume?

- Encoding: How do I anchor what I already know for rapid recall? Acronyms are an example.

Deconstruction

You can break deconstruction down into 4 pieces:

- Reducing

- Interviewing

- Reversal

- Translating

**Reducing: **Figure out the composite parts that you can break the skill down to. E.g. the Kanji characters of Japanese.

**Interviewing: **Find someone near the top, or who was at the top, that you can talk to about the skill.

- Make a list of people to interview

- Contact them and find a way to provide value in exchange for their time (e.g. interviewing and featuring them)

- Ask the questions

Some example questions (for ultra endurance running):

- “Who is good at ultra-running despite being poorly built for it? Who’s good at this who shouldn’t be?”

- “Who are the most controversial or unorthodox runners or trainers? Why? What do you think of them?”

- “Who are the most impressive lesser-known teachers?” “What makes you different? Who trained you or influenced you?”

- “Have you trained others to do this? Have they replicated your results?”

- “What are the biggest mistakes and myths you see in ultra-running training? What are the biggest wastes of time?”

- “What are your favorite instructional books or resources on the subject? If people had to teach themselves, what would you suggest they use?”

- “If you were to train me for four weeks for a [fill in the blank] competition and had a million dollars on the line, what would the training look like? What if I trained for eight weeks?”

**Reversal: **What would happen if you did things in the reverse of common practices? The best fires are built upside down, largest logs on the bottom building up to kindling. Try googling “backward” or “reverse” plus whatever it is that you’re trying to do.

**Translating: **Finding a common way to explain all the composite parts of the skill (e.g. “deconstruction dozen”) is a great way to quickly immerse yourself in the composite parts when talking to someone who is more skilled. Look for the “helping verbs,” the little tricks of any skill that let you pick it up very quickly.

Selection

Simple works, complex fails. Focus on the most important pieces that will give you as much fluency in the skill as possible. 100 well selected words give you 50% of a language.

Whatever the skill is, find the pieces that will give you the most leverage fastest.

Sequencing

It’s the burden on working memory that makes something easy or hard, and good sequencing can reduce the burden on working memory by stringing things together (see Power of Habit, Willpower Instinct).

Many effective chess players start by learning the end-game first.

There are many skills that are implicit, things the pros do without knowing it that they won’t think to teach you.

Ask:

- What are commonalities among the best competitors?

- Which of these aren’t being actively taught (i.e., implicit) in most classes?

- Which neglected skills (answers to #2) could I get good at abnormally quickly?

Stakes

How do you make failure as painful as possible? Sticks work better than carrots because of loss aversion.

See Go Fucking Do It for an easy method.

Compression

The easiest way to avoid being overwhelmed is to create positive constraints: restrict whatever it is that you’re trying to do. Take advantage of Parkinson’s Lawinstead of having it work against you.

Create a prescriptive and practice one pagers:

- A “prescriptive” one of the things you need to do, the “rules”

- A “practice” one for real world things to practice that teach the elements

Compress as much as possible to keep it all in your head.

Frequency

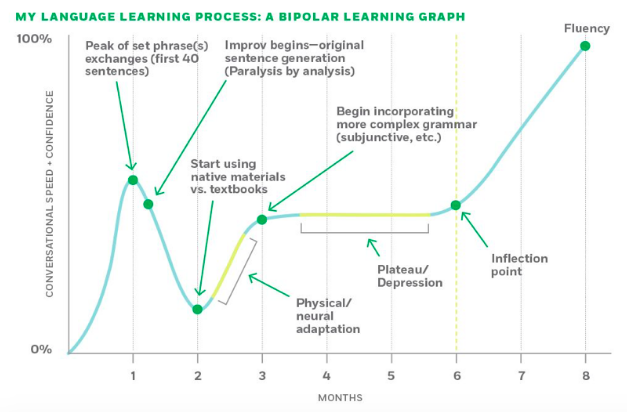

Skill learning will tend to follow a curve like this (as does company growth, relationships, other things):

Based on the curve, you can forecast setbacks, plateaus, etc.

Spanish in one month forecast:

- Sugar high @ 1 unit = sugar high @ 3.5 days (3.5 x 1), so rounding up, expect a sugar high @ day 4 of 28 days.

- Followed by immediate drop and low point @ day 7 (3.5 x 2 units).

- Rapid progress after the low point, followed by plateau @ day 10.5 (3.5 x 3), so day 11.

- Inflection point @ day 21 (3.5 x 6).

- Fluency @ day 28 (3.5 x 8).

Take breaks regularly: we remember things better at the beginnings and ends of sessions, so more breaks = more benefits from the serial position effect.

Encoding

Encoding allows you to take things you’re not familiar with and make them familiar, turn them into pieces you can attach to your existing knowledge.

Chunk things into more memorable pieces, instead of trying to remember every individual piece, or the whole thing at once.

Use a “memory palace” to remember things like numbers, cards, etc. (see Moonwalking with Einstein).

At this point, the book turns into a cookbook and the “meta learning” info is done. I’d encourage you to get it for yourself.