The Motivation Machine: How to Get & Stay Motivated for Any Goal

“We act as though comfort and luxury were the chief requirements of life, when all that we need to make us happy is something to be enthusiastic about.” – Einstein

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

Ryan has decided to learn Spanish. He downloads Michel Thomas’s tapes, buys a book on language learning, signs up for Duolingo, installs Anki, and gets to work.

In the beginning, he’s flying. He learns hundreds of words, gets the basic grammatical structures down, he even signs up for iTalki and has some conversations with natives. He’s on top of the world, confident that he’ll be speaking fluently with his Latin American friends in no time.

Two weeks in, his progress begins to slow. The gains aren’t as easy now. He has to spend as much time on reviewing the words he’s learned as on picking up new ones. The Duolingo exercises don’t feel as broadly relevant. The Michel Thomas tapes have gotten into narrow specifics around past participles and por vs. para rules. His progress slows. The high he felt at the beginning has worn off and it’s becoming a slog to learn the material. After another two weeks, it’s become such a slog that he starts missing days of practice. A week later, he has stopped entirely.

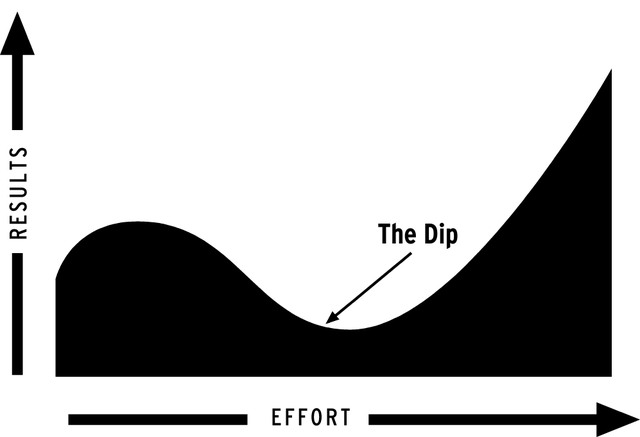

What started as a fast-paced, frenzied, exciting project hit what Seth Godin calls “The Dip”:

“The Dip is the long stretch between beginner’s luck and real accomplishment. The Dip is the set of artificial screens set up to keep people like you out… Extraordinary benefits accrue to the tiny minority of people who are able to push just a tiny bit longer than most.”

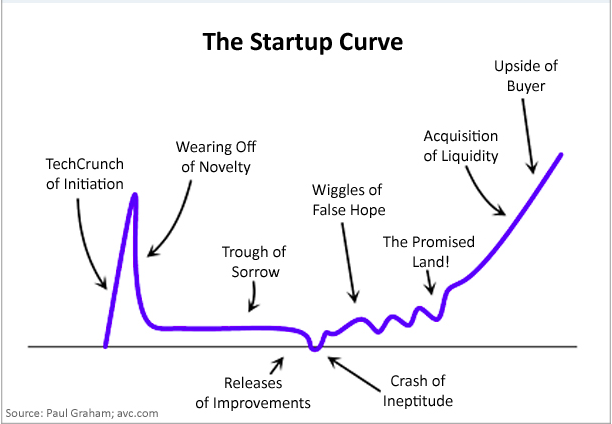

The Dip is not a new idea. Startup founders have known about it for ages, as what Fred Wilson and Paul Graham call the “Trough of Sorrow”:

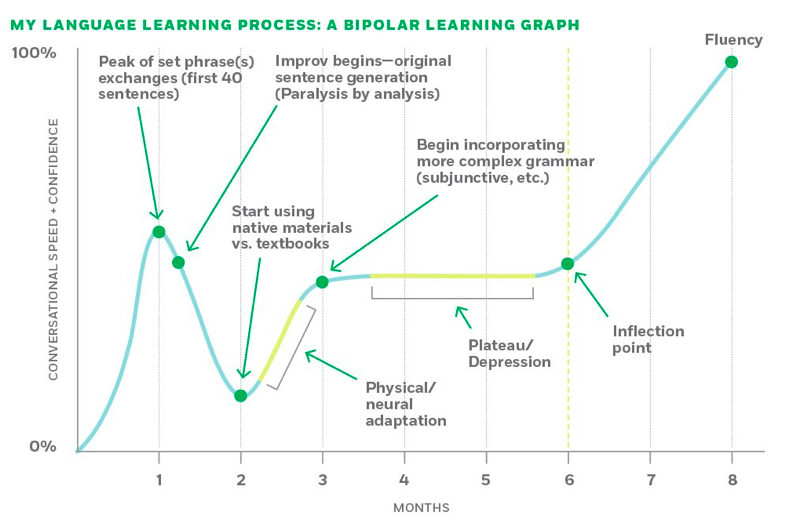

Tim Ferriss wrote about a similar curve in The 4-Hour Chef to describe his progress learning languages:

There’s a pattern here. Across language learning, company building, and any kind of creative project, there is a dip. A long period of low motivation, little excitement, and unrewarding challenges. Most people quit during the dip. But if you can manage to not quit, you can make it to the end and reap the rewards.

Discussions of The Dip leave out an equally challenging piece, though: The Start. People like Seth Godin, Tim Ferriss, and Y Combinator alums have no problem with The Start, so it gets overlooked. But The Start is a much bigger problem since you can’t reach The Dip if you don’t get through The Start, and many more people fantasize about doing something than actually do it and give up.

I began thinking more about The Dip and The Start more when I read The Motivation Hacker by Nick Winter. In the book, Winter sets out to accomplish 17 goals in 3 months, including learning 3,000 new Chinese characters, learning to skateboard, running a startup, building an iPhone app, reading 20 books, and learning knife throwing of all things.

What the book highlights is that the biggest problem we face with completing our projects isn’t productivity****or time management**,**but motivation management. When you’re sufficiently motivated to accomplish something, you’ll move heaven and earth and start a war with Troy to do it.

When you’re not motivated, no amount of SMART goals or Pomodoros or screaming affirmations in the shower will help you.

In The Motivation Hacker, Winter designed a system to ensure that he would accomplish his goals over the three months. I don’t want to spoil the ending, but he was mostly successful, and his book outlined effective motivation techniques any of can employ.

There were a couple areas he didn’t cover as much, though. First, Nick is a self-starter, so there wasn’t as much focus put on The Start as there was on surviving The Dip. Further, it was a system built for those three months, not an ongoing motivation system, though I’m sure he incorporated many of the lessons into the future.

What I want, and what I imagine you want as well, is a motivation machine where any goal we desire will be started and completed. A system for perpetual motivation based on the best practices we can find from decision science, psychology, and behavioral economics. One where The Dip is easily traversable and The Start is never an impediment.

Here’s what I came up with.

What Is Motivation?

The definition of motivation is: “The reason or reasons one has for acting or behaving in a particular way,” or rephrased, “ The general desire or willingness of someone to do something.”

Motivation is your desire and willingness to do something and to keep doing something. We need it to embark on creative projects, get in shape, make that phone call we’ve been dreading, and resist the extra glass of wine at dinner. Without sufficient motivation, none of these desires translate into action.

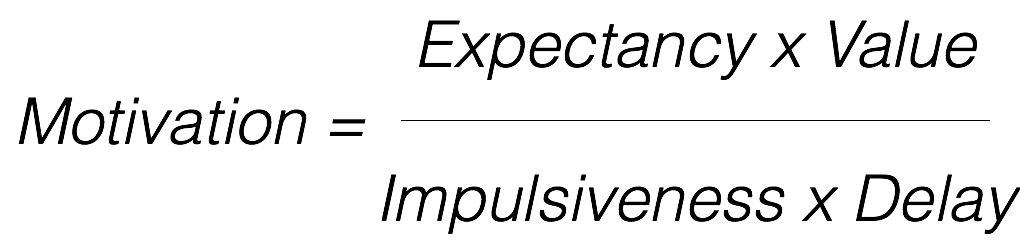

LessWrong gives us a more helpful equation:

As they describe it, your motivation is a function of your Expectancy (how likely you think you are to accomplish the goal) multiplied by the Value of the goal to you, divided by the product of your Impulsiveness (how distractible you are) and the Delay (how far off the result seems).

Consider something simple like taking out the trash. When the trash is empty, there’s no Value to taking it out, so you have low motivation to do it. When the trash is full there’s more Value, and you can reasonably Expect you’ll be able to do it, but you might get distracted by the Internet (Impulsiveness) and still not do it. It might not be until the trash is overflowing and has flys around it (very high Value to taking it out) that you can finally overcome your Impulsiveness to do it.

Or, consider learning a language. The Value may be high since you’ll be able to converse fluently on your trip to Puerto Vallarta, but your Expectancy could be low from not already knowing a second language. Layer on high Impulsiveness from your social media obsession and high Delay from the trip being months off, and you’ll be unlikely to find the motivation to practice.

Getting motivated then requires you to do some combination of:

Increasing how likely you Expect you are to accomplish the goalIncreasing the Value of achieving the goal to youDecreasing your Impulsiveness and distractibilityDecreasing the Delay by making the results of the goal more immediate

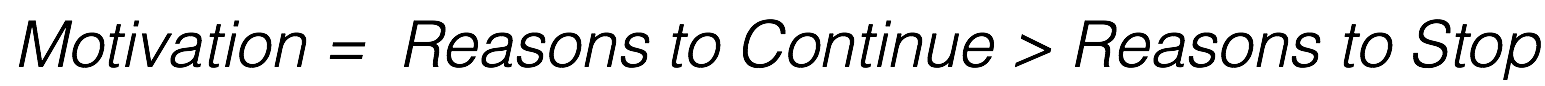

Or if you want a simpler version, you can look at how Anders Ericsson and Robert Poole defined it in Peak:

“When you quit something that you had initially wanted to do, it’s becausethe reasons to stop eventually came to outweigh the reasons to continue . Thus, to maintain your motivation you can either strengthen the reasons to keep going or weaken the reasons to quit. Successful motivation efforts generally include both.”(emphasis mine)

Whichever definition you prefer, motivation is a living system. Your reasons to continue and stop will constantly shift, as will your Value, Expectancy, Impulsiveness, and Delay, so building an effective Motivation Machine requires constantly re-tipping the scales in your favor.

We can thus break motivation down into two areas: creating motivation to get started, and maintaining motivation to continue. Some people are amazing at getting started but terrible at following through. Others are amazing at following through on what they’ve committed to, but can never quite motivate themselves to start something.

Depending on which part of the challenge you find yourself on you’ll have to more aggressively design that part of your machine. You’ll either need to make it so easy to start that you can’t say no, or make it so easy to continue that you never stop.

Getting Motivated to Start a Project

Before we continue, a clarification. When I talk about “getting motivated to start a project” I mean actually starting it. Many people will say they’re “motivated” to learn Spanish or take up basket weaving, but they never start. These people aren’t motivated, they just have an interest. They likely want to have done the project, not actually doit. Our challenge is to design a system that easily and reliably motivates you to action, instead of only talking about your interests over happy hour.

Drawing from our two equations, designing your motivation to start a project is a function of two variables: increasing your reasons to start, and decreasing your reasons to delay starting.

Increasing Your Reasons to Start a Project

If your house is on fire, you’ll be motivated to start the project of “leaving the house.” You’ll also wish you had sooner started the “fire extinguisher” project and the “second story window ladder” project. But absent the fire, you have little motivation to start either of these projects, so how do you create that motivation before your Pomeranian decides that playing with steel wool by a power outlet is a good idea?

Increasing the reasons to start a project deals with the top of the motivation equation: Expectancy and Value. We have to create ways to dramatically increase the Value of starting the project now, as well as increase our Expectancy of succeeding.

Increasing the Value of Starting a Project

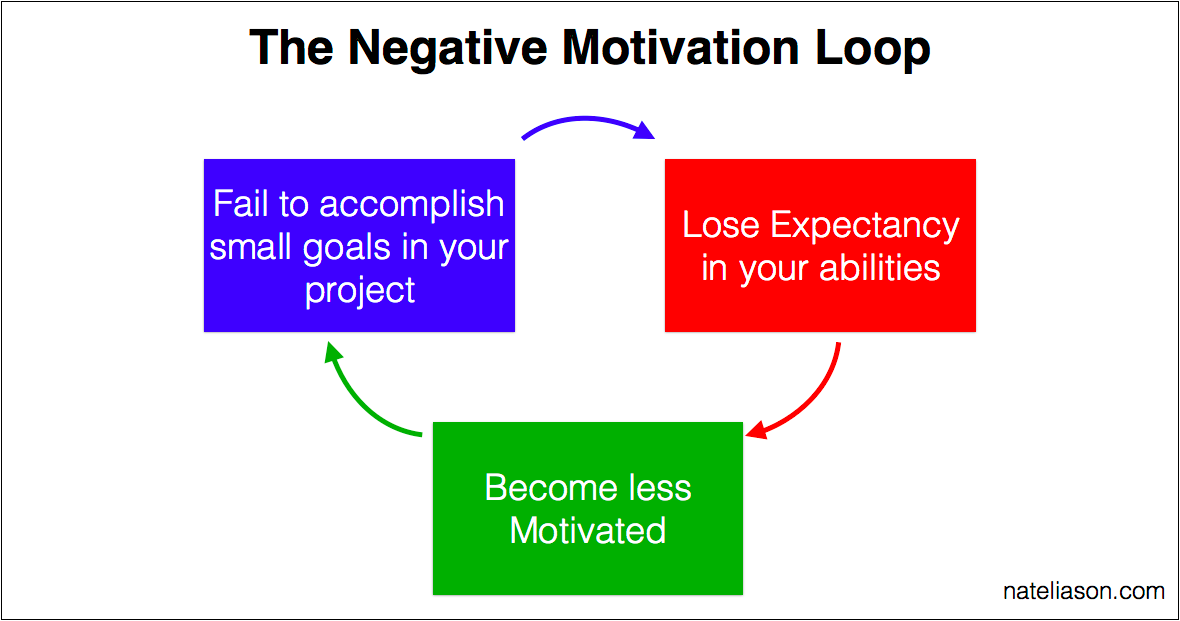

The easiest way to increase the value of starting a project is to clearly define what outcome you will get by accomplishing the goal. If your goals aren’t motivating, you may not have attached a sufficiently high value to them.

If you only want to learn Spanish because you feel like you should learn a second language, you’re unlikely to see high enough Value in it. But if you have a reason like “I spend at least a month each year in Spanish speaking places and I want to be able to make friends when I’m there,” you have a much stronger value.

If you’re trying to pick up a professional skill, “I should learn some programming” won’t get you very far. But if you’re thinking “if I learn some programming I can start building my own web apps and run them on my laptop while traveling the world like Levels” you’ll have a much higher value attached.

However you choose to frame it, focus on creating a value that is intrinsically meaningful to you. If you try to justify pursuing a goal because of something you think you should do or that you’re supposed to do, it won’t work. That’s not high value. They can’t just be goals that you have chosen, they have to be goals that were generated autonomously and that resonate with your personal desires.

The best way to increase Value is to have a specific project you want to work on. “Learn programming” is not motivating, but when you want to be able to build a certain site you have the idea for or design a mobile app you want to see in the world, you’ll be amazed at how motivated you become.

Increasing Your Expectancy of Succeeding at a New Project

Your Expectancy is how likely you believe you are to succeed at this project you’re taking on. Increasing it requires pulling two levers: decreasing your learned helplessness , and increasing the perceived ease of accomplishing it.

If you’ve ever taken on self-directed projects and failed before, or you’ve never been able to get yourself motivated to start them in the past, you may have developed a degree of “Learned Helplessness” around motivating yourself. It’s a psychological phenomenon in which repeated failures conditions you to not bother trying, even when the factors that caused you to fail in the past have been removed.

There are certain kinds of statements that give away if you’ve developed learned helplessness:

“I’m not good at teaching myself new things.”“I’ve never been good at waking up early.”“I’m just not good with languages.”“I don’t think I have the motivation to do my own projects.”“Some people are just better at getting themselves to do things.”

If those sound familiar, the only solution is to realize you’re not stuck and force yourself through the activity, or get someone else to help force you through it. This was apparently the only way to de-condition the dogs in the original experiments from their learned helplessness:

“To change this expectation, experimenters physically picked up the dogs and moved their legs, replicating the actions the dogs would need to take in order to escape from the electrified grid. This had to be done at least twice before the dogs would start willfully jumping over the barrier on their own. In contrast,threats, rewards, and observed demonstrations had no effect on the “helpless” Group 3 dogs .” – Wikipedia (emphasis mine)

Luckily, the other way to increase Expectancy helps alleviate learned helplessness as well. Part of why goals can seem unachievable (and thus low Expectancy) is that they seem too big. What does “learn programming” even mean?

To avoid this, break your goals down and keep breaking them down until they reach the point where they’re hilariously easy. If they’re easy, but still have a high value attached to them, you’ll find it much easier to find the motivation for starting.

Say you want to learn design. You find Karen Cheng’s guide to learning design, but accomplishing that whole list is a pretty big goal, so you start with the goal of getting through her first recommendation, “You Can Draw in 30 Days.” Even that might feel daunting. So you start with the goal of doing three drawing exercises from the book. That feels more achievable while still being attached to the high Value goal of becoming an employed designer.

But even with these interventions, you may still put off starting, which is why you need to decrease your reasons for putting it off.

Decreasing Your Reasons to Delay a Project

With strong reasons to start project you still might not feel like you need to do it now , which is why you also have to tackle the bottom of the equation: how to decrease the Delay (by making it seem like you’ll hit the goal sooner), and decrease the Impulsiveness (so you don’t procrastinate and do other things).

Impulsiveness isn’t such a problem when getting started since you’re more likely to get distracted and procrastinate during The Dip. Our main focus for getting started is decreasing how far off the potential end of the project seems, or framed positively, how we can make the project feel more urgent.

Increasing Urgency

By breaking the project down as we did for increasing the Expectancy, you can decrease the Delay since the smaller scope of the broken down project will have a nearer completion date. Finishing Karen’s full guide might take months, but finishing the first three exercises in the first resource might take an afternoon.

To make it more effective, though, assign a date to complete it by. “Finish the first three exercises” isn’t particularly urgent, but “finish the first three exercises by Friday” is. There are two competing philosophies for how to best do this:

The Parkinson’s Law Philosophy : The Parkinson’s Law philosophy says that you should set an artificially short deadline so you don’t waste time dilly-dallying on unimportant things. It says that by giving yourself a smaller window to complete the task in, you’ll be more likely to get it done efficiently, since “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.”

The problem with this philosophy is that while it’s good for creating more urgency and lowering your Delay if you fail to get it done in your tight deadline, you might decrease your Expectancy in the process.

The Planning Fallacy Philosophy : The Planning Fallacy philosophy says that you should set longer deadlines than you expect you’ll need since we’re terrible at predicting how long projects will take us. According to Kahneman and Tversky, only 48% of students completed projects in a time estimate based on “everything going as poorly as it possibly could.” Given this data, it seems we should double or quadruple our estimated time of completion to get an accurate view.

Which philosophy is right? The planning fallacy it turns out applies more to larger, less well-defined projects. You would have a hard time estimating how long it will take to write a book (especially if you’ve never written one before), but if you write articles a few times a week, you should have a fairly accurate view of how long it takes you to write one.

The solution, then, is to set a deadline that’sjustbelow how long it has taken you to do a similar task in the past , so that it’s motivating enough to make you start now and work efficiently (taking advantage of Parkinson’s Law) while avoiding overexerting yourself and failing (from the Planning Fallacy).

Say you’re trying to learn programming. Don’t set out to do two hours of practice a day. Set a pair of goals: at least 20 minutes of practice a day, and that you’ll finish half of the Codecademy HTML & CSS course in the next week. 20 minutes a day is reasonable to avoid the planning fallacy, but then having to finish the course in the next week will motivate you via Parkinson’s Law to be efficient while you’re practicing.

Use a Commitment Device

If you want to add an extra layer of motivation, you can also create a commitment device to prevent yourself from backing out. A commitment device is:

“…a means with which to lock yourself into a course of action that you might not otherwise choose but that produces a desired result. ”

Commitment devices usually fall into one of three categories:

Physical Commitment: Han Xin, a Chinese military general, would do this by making his soldiers fight with their backs to the river so they’d have nowhere to retreat to and be forced to fight for their lives.

In this commitment device, you physically prevent yourself from not accomplishing the goal, such as by throwing out all of your junk food, only showering at the gym, installing a site blocker like Self Control, or getting yourself banned from casinos.

Public Commitment: Elon Musk did this with the first Tesla Master Plan in 2006, and then again last year with Part 2. He told the world what they were doing, and then he had to live up to it.

In this commitment device, you state publicly what you’re going to do so that you’re motivated by the harassment of your friends if you fail to do it. The only downside is that sometimes, announcing your goals can lead to you not accomplishing them, so be sure to be specific on the outcomes and deadlines instead of saying “I’m going to write a book!”

Financial Commitment : This was popularized by Tim Ferriss in The 4-Hour Body and again in The 4-Hour Chef. He described it as the “Stakes” that you need to accomplish your goals. Without them, it’s easy to slack off and delay.

In this commitment device, you put money on the line using a site like Beeminderor Go Fucking Do It (I’ve had bad experiences with Stickk) saying that you’ll hit your goal by X date, and if a friend doesn’t verify that you did it, you lose the money. You can also simply bet someone in person, or you can have a competition (such as a weight loss competition) where the winner gets the pot of everyone else’s bets.

Getting Motivated to Start a Project Recap

Before we move on to staying motivated during a project, let’s recap the core points about getting motivated to start one:

Increase the perceived value of the project by creating a robust, clearly defined eventual outcome you’re excited about.Increase your belief in your success by starting with a small goal and identifying any symptoms of learned helplessnessIncrease the urgency of the project by creating a commitment device to follow through on it, and by decreasing how far off the first milestone is so you start sooner.

Again, there are checklists at the end to help you remind you of the finer details.

Staying Motivated During a Project

Starting is easy. Keeping going is hard. All projects will eventually land in The Dip and you’ll have to decide if you’re willing to push through to the other side, or if you’re going to quit and move on to the next thing.

Getting through the dip is primarily a function of maintaining motivation, which we can solve based on the motivation equation from the beginning and a similar breakdown from the last section. We need to make sure that we have consistently high reasons to keep going, and consistently low reasons to quit.

Increasing Your Reasons to Keep Going

To keep going, you’ll have to maintain the same or greater level of Expectancy and Value that you used to get yourself going. That will require maintaining your belief that you can achieve the goal, and keeping in mind the greater goal that you’re working towards.

Maintaining Your Sense of Expectancy in the Project

One reason that you might give up or lose motivation is if your belief that you can pull off the goal diminishes. If your Expectancy decreases too much, you may no longer feel sufficiently motivated to push through the distractions and challenges regardless of how big the potential value is.

To maintain your sense of Expectancy, keep giving yourself small wins. Keep accomplishing small bits of the project on a regular schedule so that you’re reaffirming your ability to succeed. Making a small amount of meaningful progress towards your goal is incredibly motivating. Teresa Amabile calls this the “progress principle”:

“Of all the things that can boost emotions, motivation, and perceptions during a workday, thesingle most important is making progress in meaningful work . And the more frequently people experience that sense of progress, the more likely they are to be creatively productive in the long run. Whether they are trying to solve a major scientific mystery or simply produce a high-quality product or service, everyday progress—even a small win—can make all the difference in how they feel and perform .”(emphasis mine)

It’s also a key for feeling good about your work. According to the same research, “Steps forward occurred on 76% of people’s best-mood days… If a person is motivated and happy at the end of the workday, it’s a good bet that he or she made some progress.”

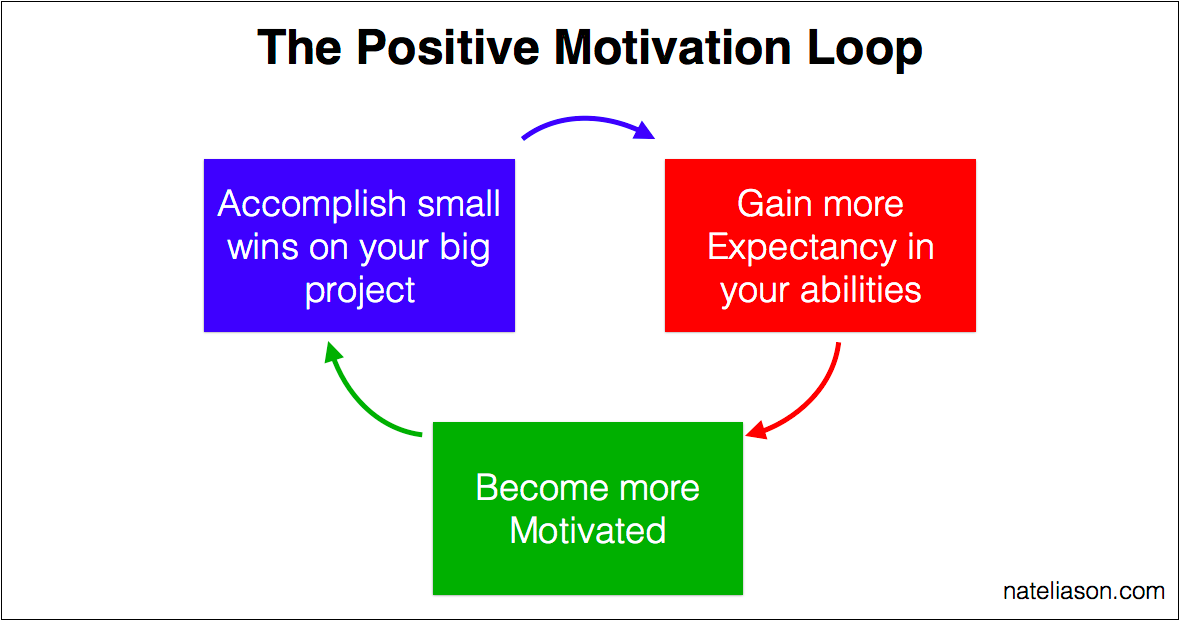

Unfortunately, the reverse is also true.

“…perceptions suffered when people encountered setbacks. They found less positive challenge in the work, felt that they had less freedom in carrying it out, and reported that they had insufficient resources…Small losses or setbacks can have an extremely negative effect on inner work life . In fact, our study and research by others show that negative events can have a more powerful impact than positive ones.”

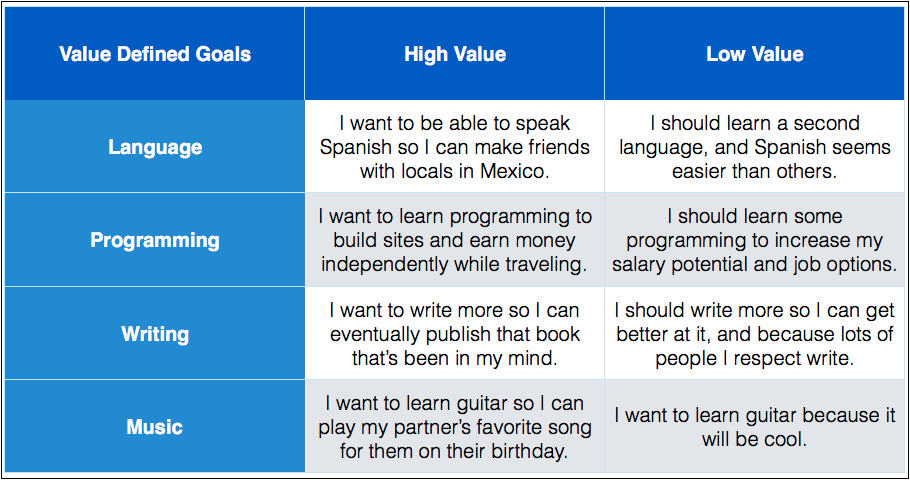

This means that there are two Motivation Loops going on with respect to your accomplishments and Expectancy. In the Positive Motivation Loop, your small wins provide greater Expectancy of future success and thus greater motivation:

But in the Negative Motivation Loop, your setbacks decrease your Expectancy of future success and lead to lesser motivation:

The solution?Set small, incremental goals that are sufficiently exciting to be motivating and which you have a reasonable expectation of hitting. A good technique for this is setting process goals instead of outcome goals. An outcome goal is great for planning, but it’s bad for day to day tracking since you can’t control your outcomes. You can only control what you do in pursuit of those outcomes.

Instead of setting a goal like “Learn Spanish,” you might set an outcome goal like “Have a 5-minute conversation with a native speaker in 3 months.” Then your daily process goal might be “spend 20 minutes on BaseLang or iTalki practicing Spanish each day.” Spending 20 minutes a day is a very doable process goal, that will lead to achieving your outcome goal and that has a greater ability to create daily small wins and move you through the Positive Motivation Loop (LessWrong refers to this as “Success Spirals”).

This Positive Motivation Loop will maintain your Expectancy and desire to continue at the micro level, the day-to-day. Now you need to make sure that you’re also staying motivated at the macro level, around the Value.

Maintaining Your Sense of Value in the Project

Your value in the project comes from whatever greater goal the project is attached to. Maybe you’re only seeing the “goal” of spending 20 minutes on Spanish practice (low Value) but you know that’s feeding into the ultimate goal of making friends with locals in Spain (high Value).

The challenge is keeping that high-level goal in front of you while you’re working through the minutia and day to day of working to accomplish it. You can do this multiple ways, but here’s what’s worked well for me.

I think of my goals on three levels: quarterly, weekly, and daily. The quarterly goals are the loftiest: finish a book draft, grow my business to > $30,000 MRR, dial in my productivity system. From those quarterly goals, I can create weekly goals as well as monthly “check-in” goals to make sure I’m on track. Then from those weekly goals, I create my daily goals, either each night when I wrap up or each morning before I get started. (For more on this, read Getting Results the Agile Way).

By having a tiered process like this, every day in my daily review I’m reminded of the weekly goals that my tasks are feeding into, and every week during my weekly review I’m reminded of the bigger quarterly goals that those weekly goals are supporting. The goals themselves are supported by “areas” (based on Tiago Forte’s “PARA” model), and those areas have the really lofty focuses: growing this blog, writing a book, getting in the best shape I’ve been in.

Each review reminds me of the higher level that the goals are feeding into and keeps them front and center in my mind so that the daily minutia is connected with a greater purpose. There are plenty of other ways to do this, but the most important part is that you do it. If you jump around from one task to the next without seeing clearly how it fits into the greater architecture of your goals, you’ll be unlikely to keep that Value front and center in your mind.

Find a way to keep reminding yourself of what your daily tasks are supporting. That’s the only way to keep the Value up.

Decreasing Your Reasons to Stop a Project

With starting a project, the challenge you had to get over was Delay: making yourself start the project now rather than later. But for keeping going on a project, the challenge you have to get over is Impulsiveness: making sure you don’t get distracted by shiny objects or minutia instead of sticking with your goal.

As such, these methods will focus on preventing distraction, avoiding procrastination, and stopping doing the “urgent unimportant” tasks instead of the “important non-urgent” ones you should be doing.

Build a Habit

The more of your ongoing projects that you can turn into habits, the easier it will be to keep a number of them going at the same time.

This is most easily demonstrated with physical goals: waking up at a set time, exercising, eating well. If you can create habits around them following Charles Duhigg’s advice in The Power of Habit, you won’t have to think about doing the day-to-day parts of the goal anymore and you’ll be much less likely to fall off the project.

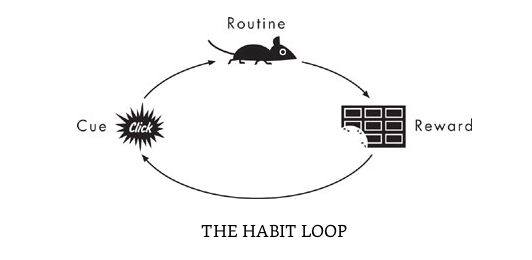

“This process within our brains is a three-step loop. First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.”

Say your goal is to lose 10lbs. You know that eating better will be a big part of getting there, so you start by building the habit of cooking dinner three nights a week. You put it in your calendar (cue) to give yourself the reminder, order the groceries in advance (cue / routine), and then do it for a few weeks, not worrying about changing what you eat (reward via small wins).

Once you have that habit in place, it will be easier to tweak the recipes you’re cooking so they’re healthier, instead of trying to both get in the habit of cooking and eating healthier. According to Duhigg, the easiest way to change a habit is to keep the Cue and Reward the same while only changing the Routine , in this case, which recipes you choose.

“That’s the rule: If you use the same cue, and provide the same reward, you can shift the routine and change the habit. Almost any behavior can be transformed if the cue and reward stay the same.”

Or, if you prefer eating out, get in the habit of eating the same thing at the same place every day for lunch, as long as it’s something healthy (you can add a second option if you want to be really wild about it).

Find Flow

The easiest way to reduce your Impulsiveness while hacking away at your project is to get yourself into a state of flow. Described by Steven Kotler in “The Rise of Superman”:

“Most of us have at least passing familiarity with flow. If you’ve ever lost an afternoon to a great conversation or gotten so involved in a work project that all else is forgotten, then you’ve tasted the experience.In flow, we are so focused on the task at hand that everything else falls away. Action and awareness merge. Time flies. Self vanishes. Performance goes through the roof. We call this experience flow because that is the sensation conferred. In flow, every action, each decision, leads effortlessly, fluidly, seamlessly to the next. It’s high-speed problem solving; it’s being swept away by the river of ultimate performance.”

It’s the experience of complete and total immersion, of being in “the zone” where you’re completely absorbed in the task and effortlessly flowing through it. If you can get into it, there’s no need to worry about impulsiveness: you won’t feel it. You’ll be wholly engaged with the task at hand.

His book on the subject is worth reading (it’s more accessible than “Flow” by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi), but the gist of getting into flow is that you need clear goals, immediate feedback, and an ideal balance between challenge and using the full extent of your abilities.

“Applying this idea in our daily life means breaking tasks into bite-size chunks and setting goals accordingly… Think challenging, yet manageable— just enough stimulation to shortcut attention into the now, not enough stress to pull you back out again.” – The Rise of Superman

And most importantly, you need total focus, or what Cal Newport would call Deep Work:

“Deep Work : Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.”

Set Clear Follow-on Goals

One challenge you may run into is not being sure what to do after you hit your incremental goals. When that happens, it’s easy to procrastinate or waste time since you no longer feel the sense of urgency that you had before, and you no longer have a clear goal and deadline that you’re shooting for.

To avoid this, lay out your follow-on goals from the start of the project, instead of only picking the first place to start. Writing out the first step will be helpful to make sure you take it, but if you only clearly define that first step, you might not continue past it, so laying out what the follow-on tasks will be will help reduce lag time between accomplishments.

Maintain Energy

The most important part of keeping your motivation high though is simply making sure you have the energy to be excited. If you’re exhausted, hungover, hungry, or out of shape, you’ll struggle to learn or work at your best.

If you develop a lifestyle that supports your efforts, you’ll have no difficulty keeping your motivation levels high. I shouldn’t have to explain in too much detail since you already know what this entails:

Optimize your sleep (8 hours, dark, regular wake up time, etc.)Cut back or quit drinkingAvoid sugar and excessive stimulantsWalk and exercise dailyEat lots of plants, meats, fats

You know the drill.

Building Your Motivation Machine

Pulling together the information from this article, you now have a simple system you can use on a daily basis to give yourself the motivation to start new projects, keep working on what you’ve committed yourself to, and break through the learning and progress plateaus that will happen along the way.

First, figure out what you need to do:

Do you need the motivation to start? Or do you need the motivation to continue?

If you need the motivation to start:

Clearly define an exciting, high-level value to starting the projectSet small, easily achievable goals for the project to startCreate a deadline for the first goal that’s motivating without being overly ambitiousPre-commit yourself to accomplishing the goal using a commitment device

If you need the motivation to continue:

Keep setting intermediate process goals that you know you can achieveRegularly remind yourself of the greater vision your daily goals are feeding intoBuild a habit around the goal so you keep working on itFind the sweet spot within the process that gets you into flowClearly define your follow-on goals so that you know where to go nextKeep your energy up with good lifestyle habits

With these processes, you should have no issue getting over The Start and working through The Dip.