Enjoy the Process: Your Intrinsic Motivation Happiness Machine

Early on in life, we’re first told:

“You should do X because Y.”

In some cases, Y makes sense: “You should shower because you don’t want to smell bad.” In others, it might not make sense and be frustrating instead: “You should stop asking so many questions because it’s annoying.”

The “Do X because Y” phenomena that we encounter most come from school and work. “You should study so that you get good grades.” Then, “You should get good grades so you can go to a good college.” And then, “You should get good grades at your good college so you can get a good job.”

Eventually, you graduate to “You should do your job so that you continue to get paid.” And, “You should do your job well so you get promoted.”

We develop and maintain the habit of Doing X Because Y , and this extrinsic motivation (a term popularized in Drive) propels most people through life. So long as we continue to receive the Y, we continue to do the X.

But, over time, we can get bored and start to dislike that process more and more.

That job that was exciting at the beginning is now frustrating and repetitive. That perfect GPA that was rewarding the first semester is now a source of neurotic obsession. That higher income which was great for a few weeks has just given you a new set of wealthy neighbors to compare yourself against.

While Do X So that Y got us started, eventually, the excitement and reward from Y fade and we start to enjoy X less and less along with it.

The Problem With Goals and Novelty

When I started this site a year and a half ago, it was a wonderful day if I received more than 100 visitors. A year ago, I set a record of 1,600 people visiting in one day. 6 months ago, a great day was 5,000 visitors. Now if fewer than 10,000 visit, I’m disappointed. Despite thinking that more readers will make me happier, every time it happens, I’m quickly back to the same level of satisfaction (and anxiety).

I’m not alone in this. The concept of the “Hedonic Treadmill” goes back as far as Stoicism and early Virtue ethicists (e.g. Aristotle), who espoused developing an internal, personally grounded happiness not tied to the acquisition or possession of anything external to you. When Seneca says that “It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor,” it isn’t an admonishment of wealth, rather, a recognition that by pegging your happiness to something above what you already have, you’re continually dissatisfied.

Philosophers were able to figure this out a priori , and now we have the research to back it up. We know that lottery winners and paraplegics regress to the same rough happiness level as before, and we know that earning a higher wage doesn’t make you any happier too. It also seems that the marginal improvement to your emotional well being from increased income plateaus around $75,000 (though this varies by savable income).

Money is an easy tool for this analysis, but this phenomenon extends to other achievements as well. As soon as you hit a goal at work or in life, you barely savor it and there’s suddenly another one to shoot for. You’ll lose weight till you hit the goal, then stop dieting and gain it back. You’ll save up for that new car, then get used to driving it two weeks later. As soon as you hit the Y, the excitement will fade and there will be a new Y to shoot for.

Or, worse, you’ll become depressed, bored, and listless after getting Y. Olympic athletes have major struggles with depression after the games, since that Y they were Xing towards for 4 years is now suddenly gone, whether or not they got a gold.

But, we forget this. Most of us have some financial goal around “earn more.” Or to grow our business bigger, or to publish more, or to get more Twitter followers, all operating under the belief that “ Once I reach Y, life will be better.”

But, by tying our happiness and satisfaction to these goals, we end up spending most of our time grinding away in pursuit of future happiness, with brief periods of satisfaction if we’re successful. As Scott Adams puts it: “…goal-oriented people exist in a state of nearly continuous failure that they hope will be temporary.”

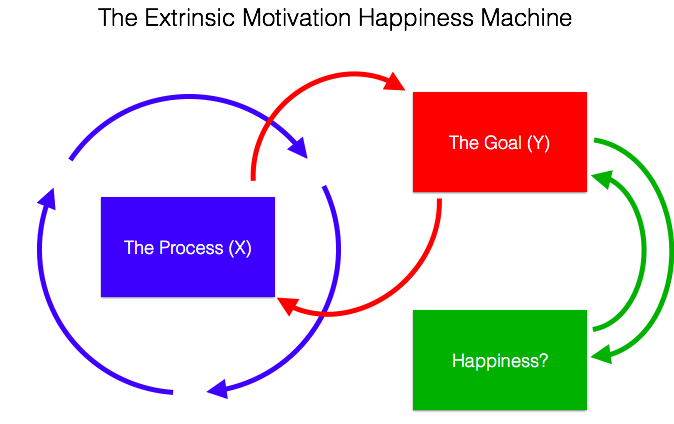

The Extrinsic Motivation Happiness Machine

The problem so far has been our tendency to focus on “ Doing X Because Y”. We have the goal, Y, and then the process, X, that we do in pursuit of Y. But, as we’ve seen, this ends up causing us to spend most of our time in some form of dissatisfaction, striving for the Y that we think will make us happy, interrupted by brief periods of satisfaction.

Let’s call this our extrinsic motivation happiness machine:

We have our process going continuously (X), which occasionally results in hitting our goals (Y), and then those goals lead to brief happiness (hopefully). Then that happiness goes back and informs new goals, which go back to adjusting the continuing process.

This is what most of us base our pursuit of happiness on. This long process where we Do X Because Y, then hope that Y will result in happiness. And from our idea of happiness, we create our goals Y and then create the process X to get there.

But, as we now know, this is deeply flawed. The happiness from hitting our goals won’t last, and worse, we have no idea what will make us happy in the first place, so we can’t even set good goals!

What’s the solution? Skip the goal-dependent part of the machine entirely, and focus on enjoying the process.

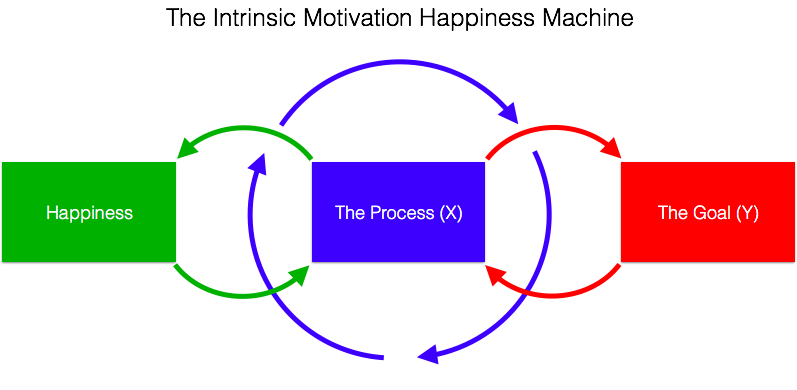

Enjoy the Process: Your Intrinsic Motivation Happiness Machine

When I first started working out, it was mostly to look better naked. I’d realized how big of a difference it can make in attractiveness for men, so I set a goal to reach a certain weight and body fat percentage, worked towards it, and achieved it.

But… then I quit. I hit my goal, then stopped. A year later, I started again, hit my goal, then quit. This repeated itself two more times until I arrived at my current system: not setting fitness goals at all. I have directions I point in, but I know that if I have a set goal with it, I’ll focus too much on that instead of enjoying the exercise itself.

The same goes for my writing. While before, I focused intensely on pageviews and rankings, I don’t worry about it so much now, and instead, focus on enjoying the process of writing. Not just because that lets me always have fun with it, but also because that tends to produce my best work.

The strongest articles on this site are the ones that I had the most fun writing, such as the Decomplication or Lifestyle Business or Drugs or Lasting Longer in Bed ones. I set them up to do well, yes, but that wasn’t the point. I enjoyed writing them regardless of how well they were going to do.

Instead of using the Extrinsic Motivation Happiness Machine, I was using the Intrinsic one:

This is the only way to do intense, sustained, productive work long term and not be miserable. If you tie your happiness to the outcomes of some deferred life plan, as most people do, then you spend so much of your time thinking about hitting the goal that you miss out on all the fun along the way.

But, by focusing on enjoying the process, you get to be happy and have fun all the time, regardless of whether or not something works out. So long as the ship is pointed in the right direction, you can enjoy the entire ride, instead of fretting over optimizing the sail positioning.

This also gives you a good barometer for what you should be working on. If you’re doing something primarily for the end reward, you have to recognize that the extrinsic motivation won’t last and won’t make you nearly as happy as you expect. Worse, you’re going to get sick of the process, quit, or procrastinate heavily. As much as possible, you want to avoid spending your time on something completely directed towards a reward, because you’ll end up spending most of your time unhappy or dissatisfied.

Instead, find those processes where you completely lose yourself, and where you’ll have had fun regardless of the end result. If you can do that, then you’ll be continually happy either way and not be stuck hoping that you’ll be happy later.