How to Use Deliberate Practice to Reach the Top 1% of Your Field

In the late 1970s, Anders Ericsson devised a very boring experiment.

His subject, Steve Faloon, was instructed to memorize random strings of numbers. Ericsson’s interest was in how many numbers Steve could keep in his head with consistent practice. The research and common wisdom at the time said you could only hold around 7-8 random bits of information in your head at a time, and so far, Steve was proving the research.

In each session, Ericsson and Steve would sit down, and Ericsson would read him a random string of numbers at a rate of one per second. By the end of their fourth, one-hour session together, Steve could reliably recite back strings of 7 or 8 digits, but he’d struggle with 9, and never successfully remembered 10.

Until he made a breakthrough.

During their fifth session, Steve succeeded at remembering his first 10 digit string and followed it up with his first 11 digit string. It may seem trivial, but when the average person (including Steve at first) can only remember 7, this is a 57% improvement over average.

Steve was only getting started though. He and Ericsson continued their work together, and by the end of the 200th(!) session, he could reliably memorize strings of 82 random digits.

He didn’t have any gift, he didn’t receive any special training, he simply practiced, week after week, in a special way. The same way that’s created chess prodigies, world record holders, Olympic gold medalists, prolific writers, and any master of their craft that you’re familiar with today.

Anders Ericsson devoted his life’s work to studying this technique for effective skill development and coined the term “deliberate practice” to describe it.

If you feel you’re already very familiar with deliberate practice and just want some examples to get some ideas flowing for how to improve your skills, check out my catalogue ofdeliberate practice examples.

What is Deliberate Practice?

If you’re reading this blog, then my guess is that this isn’t the first time you’ve heard of deliberate practice. It’s very much in vogue in the learning community, ever since the research on it was misinterpreted by Malcolm Gladwell in Outliers.

But I don’t feel that most sources have done the topic justice. Until recently, most of the books discussing deliberate practice have had to interpret it themselves, as done in Talent is Overrated ,__The Talent Code ,__The Practicing Mind ,__The First 20 Hours , and Outliers , and when you read Ericsson’s original work outlined in his book Peak , it’s clear that he feels he’s been misunderstood.

Here, I’m going to explain deliberate practice and how anyone can use it for their own skill development drawing solely from Ericsson’s work. I recommend you pick up Peak anyway since it’s a fantastic book, but this article should serve as a sufficient primer.

This is one part of a 7-part masterclass on teaching yourself anything. If you want the other 6 parts, you can get them for free here.

Naive vs. Purposeful vs. Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice is a method of practicing primarily aimed at rapid, continuous improvement. Its goal is to avoid getting trapped on learning plateaus and to keep progressing as effectively as you reasonably can.

It can best be understood at first in contrast to the “naive” practice that most people engage in.

Naive Practice

Naive practice is what most people are doing most of the time when they’re practicing. They’re going through the motions, repeating what they normally do with the skill, without being challenged or having a set goal.

This might include:

- Playing tennis, chess, scrabble, or any other competitive game casually with a friend

- Writing the same type of articles you normally write

- Playing music you already know how to play

- Practicing a song, but continuing on when you miss notes

- Looking up a recipe, baking a pie, and then keeping making that kind of pie in the future

The problem is that in this kind of “practice,” you’re not improving or challenging yourself. As Ericsson says:

“ People often misunderstand this because they assume that the continued driving or tennis playing or pie baking is a form of practice and that if they keep doing it they are bound to get better at it, slowly perhaps, but better nonetheless… But no. Research has shown that, generally speaking, once a person reaches that level of “acceptable” performance and automaticity,the additional years of “practice” don’t lead to improvement . ” (emphasis mine).

Then the question, of course, is what do you do? If you recognize that you’ve reached that plateau where you’re not really improving, just going through the same automatic motions over and over again, how do you move up to the next level?

Enter purposeful practice.

Purposeful Practice

Purposeful practice is one step below deliberate practice, but it’s far superior to naive practice.

Contrasted to Naive Practice, Purposeful Practice has a few key characteristics:

Purposeful Practice Has Specific Goals : While in Naive Practice you’re hitting the ball, playing a game with a friend, running through the same routine, in Purposeful Practice you set specific, narrower goals for what you want to successfully do.

These goals could sound like:

- Play this piece all the way through, at this speed, with no mistakes, three times in a row

- Land 20 serves in a row inside the box

- Remember 10 digits in a row

- Program an email signup form without checking Stack Overflow

- Run 10 100m sprints in under 12 seconds each

This is an area where SMART goals come in handy. Obscure goals like “get better” won’t be useful, but by making your goals specific, measureable, actionable, relevant, and time-bound, you can make small improvements that will over time lead to big improvements.

Purposeful Practice is Focused : Whereas you might be distracted in naive practice, purposeful practice requires your complete undivided attention. It requires Deep Work.

Purposeful Practice Involves Feedback: The only way you can improve is if you have some idea of how you’re doing relative to your goals and what parts you need to improve on in order to get closer to your goals.

For Steve, this was the correct/incorrect result when he tried to repeat the numbers back, but also his own self assessments of what was easy or difficult with each string. For some skills, like tennis, you either need a coach who can show you what you’re doing wrong and how to correct it, or you need to videotape and critique yourself in order to improve your performance.

However you do it, feedback in some form is necessary, and the more often and precise the feedback, the better.

Purposeful Practice Requires Getting Out of Your Comfort Zone : If you never push yourself beyond what you’re already capable of, you can never improve. Ericsson gives an example of how he did this with Steve:

“As he increased his memory capacity, I would challenge him with longer and longer strings of digits so that he was always close to his capacity. In particular, by increasing the number of digits each time he got a string right, and decreasing the number when he got it wrong, I kept the number of digits right around what he was capable of doing while always pushing him to remember just one more digit.”

This is a perfect example of how you want to get right up to the edge of your abilities so you’re challenged, but not so far beyond your capabilities that you’re overwhelmed. If they had started at 20 digits Steve would have given up. But by increasing his load 1 digit at a time, he got progressively better and it never seemed too challenging.

Purposeful Practice Requires Creative Problem Solving : Occasionally you’ll run into barriers where it feels like you can’t get past that next threshold. At these points it’s best to try differently , not necessarily harder.

For example, with Steve, he hit a barrier at 22 digits, so he changed up how he was memorizing them in 3 and 4 digit chunks.

When he hit another barrier, Ericsson slowed down how quickly he read out the numbers, then slowly worked back up to normal speed, and Steve broke through.

At another barrier, Ericsson increased the number of digits he was giving Steve by 10 to completely overload him, but to both of their surprise, Steve remembered a significant portion of them which gave him the motivation that he could keep doing better.

Purposeful Practice in Summary : According to Ericsson: “Get outside your comfort zone but do it in a focused way, with clear goals, a plan for reaching those goals, and a way to monitor your progress. Oh, and figure out a way to maintain your motivation.”

To make it deliberate, you need two more variables.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate Practice is the same as Purposeful Practice, but with two key differences.

Deliberate Practice is in a Well-Defined Field. Deliberate practice requires the field be well developed and rigorous enough that there are clear differences between experts and novices.

This would include fields like musical performance, chess, ballet, diving, almost anything that’s competitive and been around for a while. What doesn’t qualify is non-competitive tasks like gardening, many hobbies, many common labor force jobs like engineering, consulting, teaching, and anything where you can’t show clear criteria differentiating experts from intermediates from novices.

Deliberate Practice Requires a Teacher Who Can Tailor Practice Activities. You need a good coach who can provide the practice strategies that help you develop the areas you need to, based on the feedback they provide.

Ericsson makes the distinction a little clearer:

“… we are drawing a clear distinction between purposeful practice— in which a person tries very hard to push himself or herself to improve— and practice that is both purposeful and informed. In particular, deliberate practice is informed and guided by the best performers’ accomplishments and by an understanding of what these expert performers do to excel.Deliberate practice is purposeful practice that knows where it is going and how to get there . ” (emphasis mine)

He also says, though, that you can still get many of the benefits of deliberate practice without having a personal coach. Memory competitors study the techniques and methods of the grandmasters and use those techniques to design their own study methods, so even though they don’t have a coach, they’re still getting the benefit of the experience of their predecessors in the field.

For anyone who wants to take advantage of deliberate practice but doesn’t have access to a personal coach, he gives this formula:

- Identify the expert performers in your field

- Figure out what they do that makes them so good

- Design purposeful practice around learning how to do that yourself

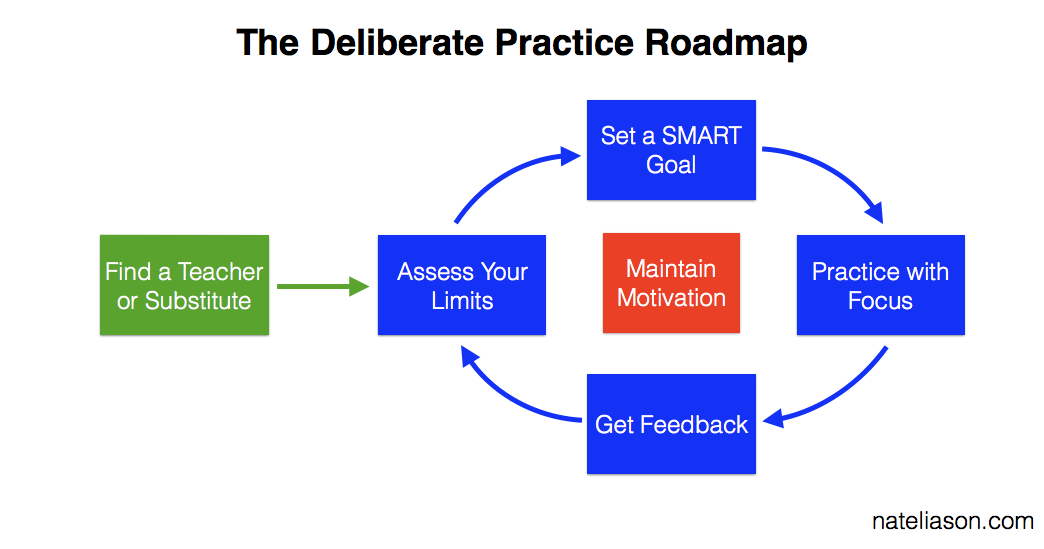

Putting it All Together: A Deliberate Practice Roadmap

Now that we understand the components of deliberate practice, we can put them together into a roadmap for applying it to any skill.

Before Starting: Find a Teacher or Substitute Teacher

To truly engage in deliberate practice, you need a teacher or a coach who can guide your learning process. They should be able to give you small, specific goals to improve parts of your craft and point out where you might be weak.

If you don’t have access to a direct coach for your skill, either because of money, location, or the skill not being well suited to a teacher, you have to figure out a teaching substitute on your own. The main value of a teacher is in the tailored practice, goal setting, and feedback, so you have to reproduce that on your own.

That means you need to find an expert in your field who you can study and try to emulate, you need to set small, concrete goals for improving parts of your skill, and you need a feedback mechanism to figure out where in the skill you’re weak.

Once you have a teacher or an effective feedback and goal setting method, you can start the deliberate practice loop.

Step 1: Assess Your Limits

Figure out where the boundaries of your current skill level are. What’s the weakest part of your writing? How much weight can you lift? How fast can you run? What programming functions do you know off the top of your head? You need to get an idea of where you’re weakest or most want to improve.

Step 2: Set a Reaching, SMART Goal

Pick the area of your skill that you feel the most limited by, and set a goal to improve that aspect. The goal should be just beyond your current capabilities in order to stretch you, but it should not be so far beyond where you are now that you’re overwhelmed.

This could be playing a piece without errors three times in a row at a certain speed, lifting 5 additional pounds, writing a 1,000-word article within a time constraint, running 400m a few seconds slower, whatever you feel you want to improve.

Step 3: Practice with Focus

Start practicing with that goal in mind, and give the practice your complete focus. You can’t be distracted or doing multiple things, you need to give it your undivided attention to get the full benefits.

Step 4: Get Feedback

During your focused practice, you need a feedback mechanism for how you’re doing relative to your goal. This will ideally be a skilled teacher or coach who knows what to look for, but you can also devise your own feedback methods based on the criteria discussed above. Either way, a feedback system is necessary for knowing where you need to improve.

As you go, your feedback mechanism will inform you how you of where your weaknesses are (step 1) and help you set better goals (step 2), but it will also help you identify when you’ve hit plateaus which require their own special method of goal setting.

Maneuver Around Plateaus

As you keep moving through the deliberate practice loop, you’ll get stuck at skill level plateaus. When these are encountered, you need to creatively maneuver around them instead of throwing more work at them. This is done by stressing your body and brain in new and different ways relative to the skill. For example:

- Making yourself type 20wpm faster to get your fingers used to the feeling, while letting yourself make errors

- Making yourself type 10 wpm slower , but with perfect accuracy

- Changing the kinds of exercises you’re doing for weight lifting

- Removing some chess pieces from the board to focus on others

- Not letting yourself use certain kinds of words in writing (e.g. adjectives)

- Roll against a better Jiu Jitsu practitioner than you usually do

By stressing yourself in new ways, you’ll notice which parts of the skill are holding you back so that you can tailor your training to those pieces.

And the last piece:

Maintain Motivation

People stop improving because they stop pushing themselves, and because they lose motivation to continue improving at the skill. They reach a point where they feel like they’re “good enough” and the perceived benefit of trying to get better is outweighed by the perceived benefit of relaxing.

You, therefore, need to weaken your reasons to quit and strengthen your reasons to keep going. Ericsson gives a few ideas for how to do this:

- Keep yourself in shape by staying active and sleeping well.

- Remove things from your environment that could pull you away from practice, such as your smartphone.

- Building a habit around your practice, such as by doing it first thing in the morning.

- Limit your practice sessions to an hour to avoid burnout.

- Celebrate your wins to motivate yourself to keep improving.

- If you fall below a plateau, commit to yourself that you’ll get back to it before quitting.

- Put together a group of people working on the same thing so you can motivate each other.

With these four steps and two external pieces, we can create a diagram for deliberate practice:

And there’s your roadmap. Study it, internalize it, return to it, keep pushing yourself beyond your comfort zone, and in time, you’ll become a true master of your craft.

If you want more examples of ways to use deliberate practice on your own, check out the companion article to this one where I’m listing as many deliberate practice examples as I can find or think up.