A Simple Exercise to Discover What Skills You Should Learn

I’ve written at length about how to self-educate, how to move through the levels of expertise, and how to practice your skills more effectively, but I’ve said little so far on how to choose what you ought to learn.

Most college students prioritize what they learn based on what they, or their parents, think will earn the most money. The myth says that outside of a few areas, it’s hard to earn a good living. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

At a reasonable level of ability in most skills, you can charge enough to make a comfortable living as long as you think beyond the limited mindset that your peers and parents are confining themselves to.

A skill only needs to meet a few criteria to have the potential to become your career:

It needs to be a skill that pays money in a reasonable way. This way does not have to be obvious, though. Even skills as obscure as Hacky Sack could generate a comfortable income by teaching other people how to be expert hackey sackers, building a YouTube audience around it, selling online courses about it, and so on. There’s almost always a way to make a skill profitable if it’s something other people need or want to get good at.

It must be a skill you enjoy learning. Do not pick a skill because you think it’s what you should learn or it seems safe. Pick one that you like working on, that you’ve liked exercising in the past, and that you could see yourself continuing to pursue.

It must be a skill you can start developing on your own. Certain skills won’t be feasible as starting points, and you’ll have to reduce them to good places to begin. Dolphin training, for example, will be hard to do without a pet dolphin. But that doesn’t mean you can’t start practicing animal training at the local dog shelter.

The last thing you should keep in mind is that you don’t need to find the perfect skill or set of skills, that you want to focus on for the rest of your life. Your interests will change over time, and you don’t want to plan the rest of your life based on a decision by an 18-year-old. Instead, think of this as a place to start. Your goal is simply to find a skill you’re interested in enough to move on to the Sandbox Method for self-education.

How to Identify Skills to Start With

To find what skill or skills, you may want to start learning, take a few minutes to go through this exercise.

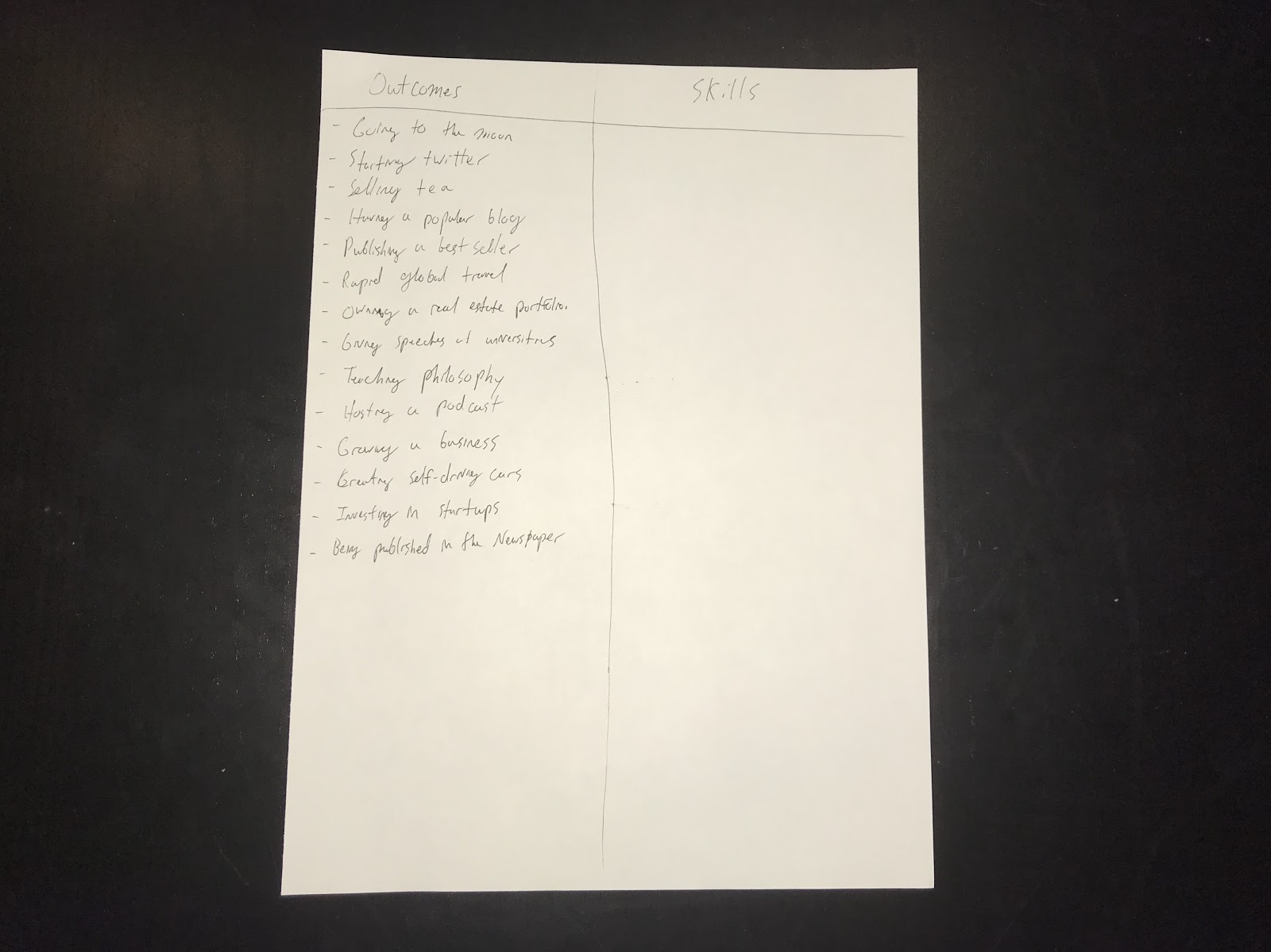

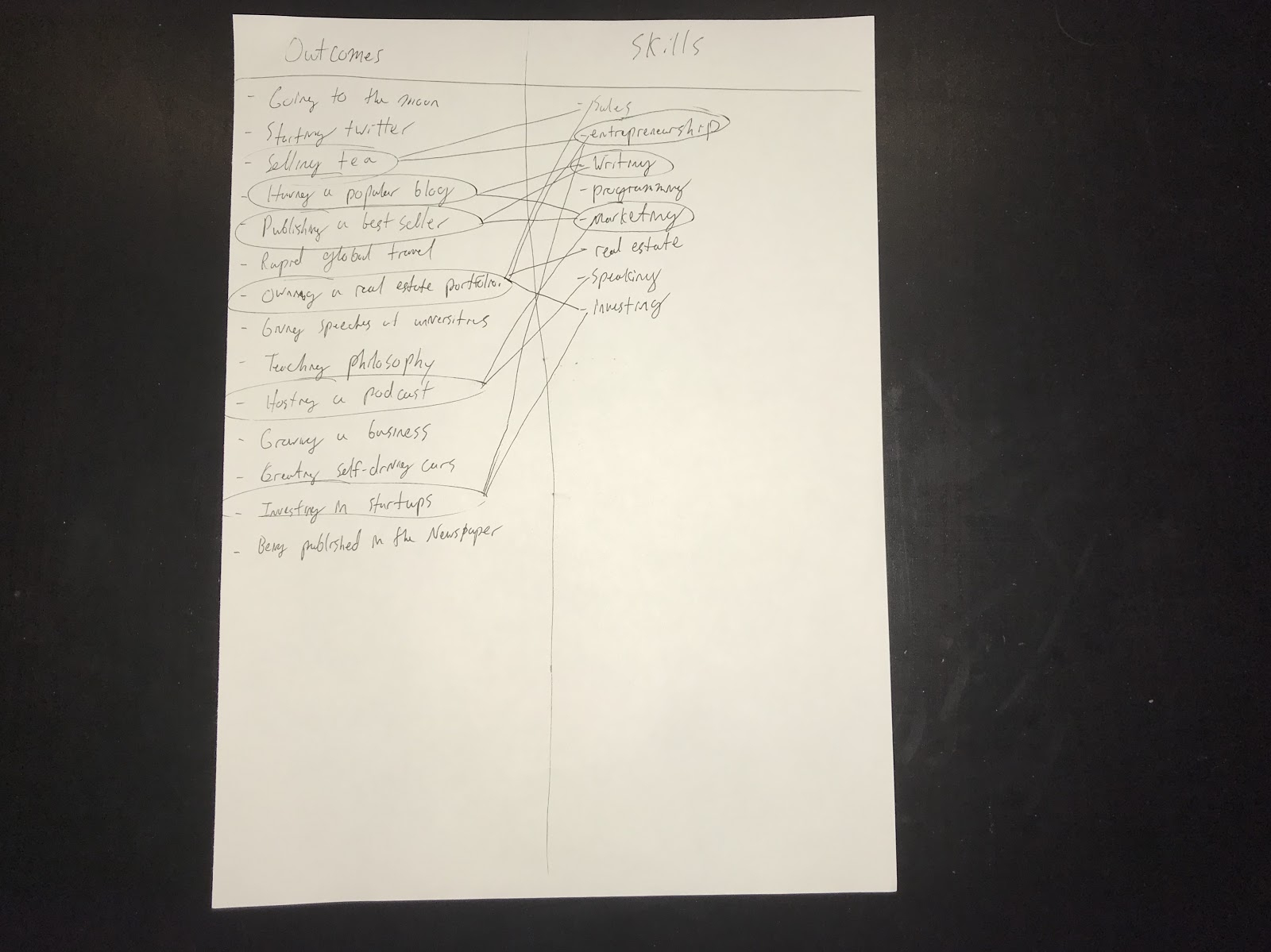

First, get a piece of paper, and break it into two columns. On the left side, at the top write “Outcomes” and on the top of the right, write “Skills.”

The outcomes side is a list of every kind of creation in the world that you admire. Anything that you would have loved to be a part of, contribute to, do for yourself, or understand. This could include going to the moon, creating Facebook, writing a book, organizing a music festival, designing headphones, filling the Louvré any outcome that you’re interested in.

Take three minutes and fill out the left side of your sheet with as many outcomes as you can think of in that amount of time. If you get stuck, ask yourself these questions:

- Whose work do you admire?

- Whose lifestyles do you aspire towards? What do they do for work?

- What in your environment would you have loved to help make?

- What did you love doing as a kid?

- What one big accomplishment from the last 100 years would you love to have gotten credit for?

Don’t filter your outcomes as you’re going. Just write down everything that comes to mind. Even if it seems silly.

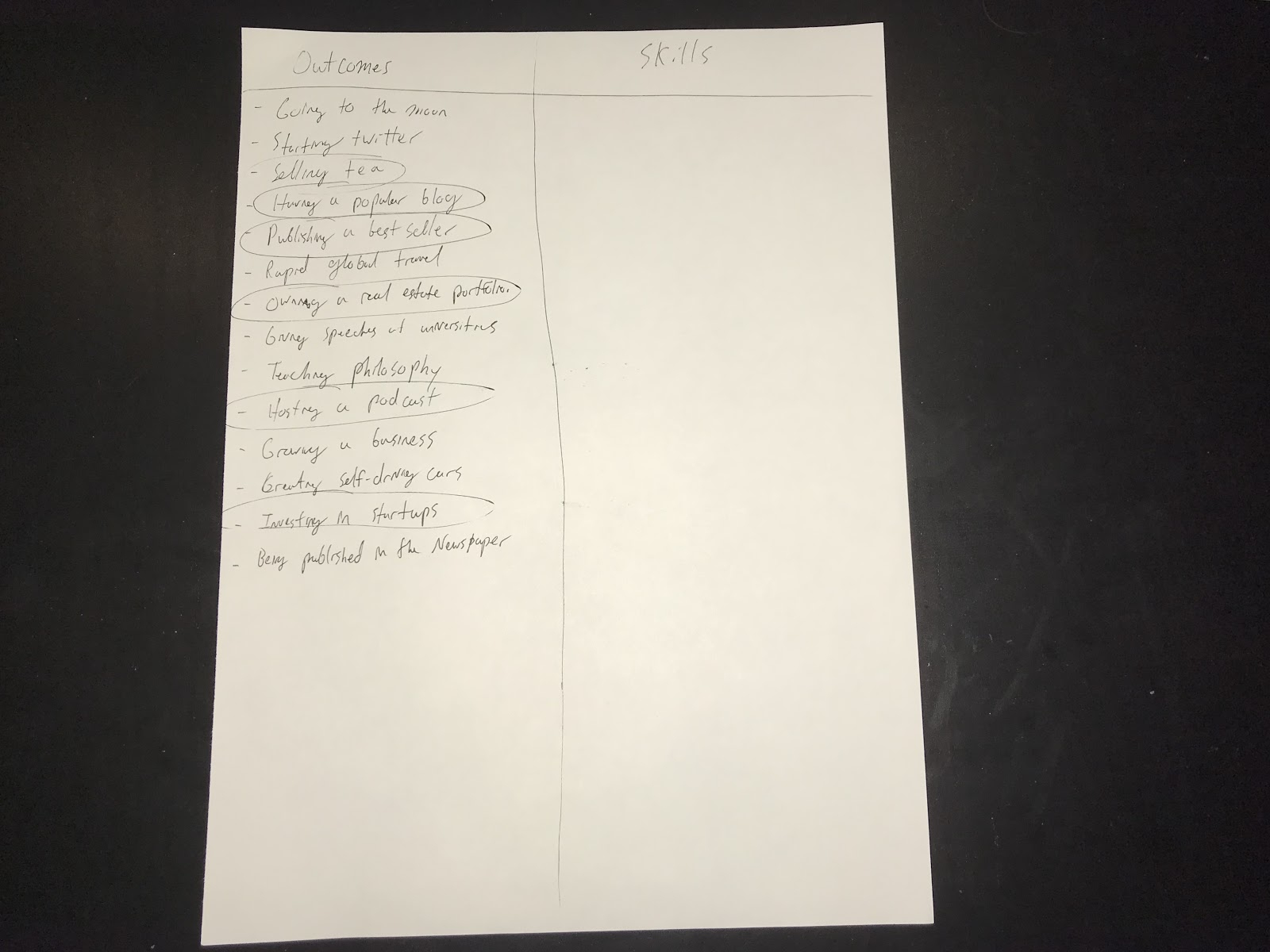

Once your three minutes are up, take a minute to go back through and circle the five to ten outcomes that are the most exciting, most motivating. Do not worry about what seems achievable! This is only to help guide your personal skill development—you don’t have to worry about not being as smart as Elon Musk.

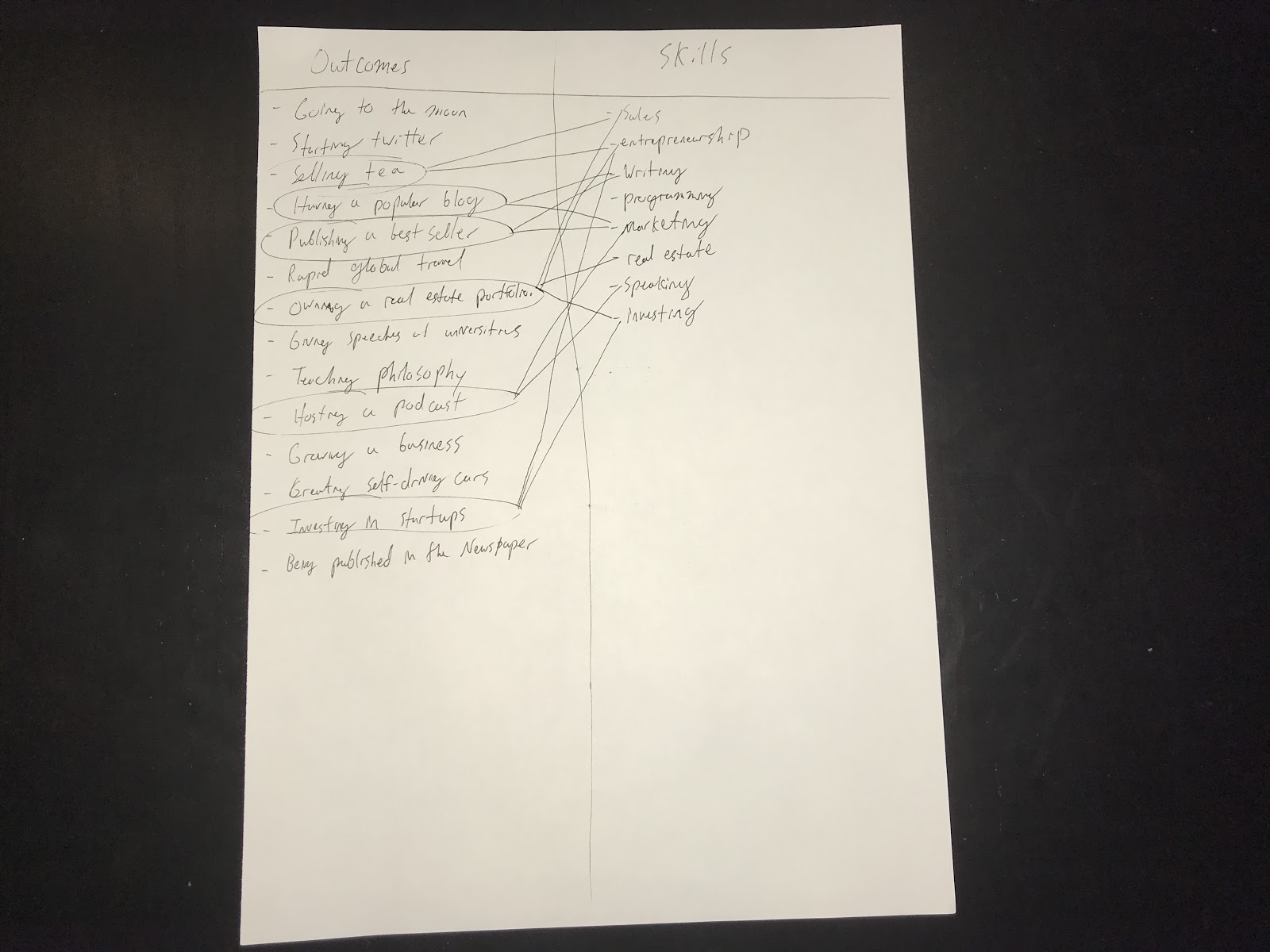

With your list of five to ten outcomes, the next step is to figure out their composite skills. For each circled outcome, list out every skill related to achieving that outcome, across however many people it takes to create it.

Some of them will only have a few skills. Writing a book, for example, mainly breaks down to writing. But an outcome like “put someone on the moon” (considering everyone involved) breaks down into leadership, management, mechanical engineering, aeronautical design, sales, finance, physical endurance, electrical engineering, computer science… the list goes on.

As you add skills to the “skill” side, draw a line from each circled outcome that depends on that skill.

If you’re not sure about the technical term for something, don’t worry about it. Just put the closest you can come up with to what sounds like a skill. And if a skill comes up more than once, don’t skip over recording it. Having it more than once will be helpful.

Now from your list, narrow it down to three skills based on a few criteria:

- What skills popped up the most?

- What skills excite you the most? Go based on what pulls you in, not what you push yourself into.

- And what skills are learnable? Leadership might be interesting to you, but it’s harder to start landing work for than something more tangible like programming. You can still learn leadership, but you may need to focus on something tangential and more sellable in the short term (in this case, perhaps sales).

Don’t worry about getting this perfect right away. You can always go back and do the exercise again or update it. And you should! Your interests will evolve constantly throughout your life. The goal right now is to give you a place to start; to pick a few skills you can begin learning and start getting more data from.

And don’t think too hard about which three youshouldpick. Go with the three youwantto pick. If you have sales on there but you’re telling yourself “oh I’m not a salesperson” you have to resist those thoughts. It’s only accurate to say that you haven’t learned sales yet, not that you can’t learn it. Imagine a nine-month-old child saying “oh I’m not a walker.”

Go with the three that get you pumped up, excited, that make you say “yes, I would love to learn how to do this. Even if you’ve never done something remotely close to it, don’t worry about that. Everyone has to start from zero at some point.

Pick the skills that get you fired up, not the ones you think you should pick or that will make your parents happy.

5 Common Broadly Useful Skills

You may feel a bit stuck in the last exercise, which is fine. If you’re not sure what skills you want to focus on, then taking a look at some of the common, broadly useful skills that graduates have used to give themselves jobs and lives they’re excited about will help.

These are the five skills that seem to be the most useful for having control over your post-grad life, while also providing the opportunity to grow into learning larger macro-level skills (like entrepreneurship, project management, leadership).

There are certainly useful skills beyond the ones listed here, but these ones lend themselves to being easily self-taught within a college or post-grad environment. In each case, you could reach “employable” level in less than six months if you’re motivated.

Programming

(Examples: Bekah Lundy, Max Friedman, Darwish Gani)

Programming is the best example we have of a skill that’s highly valuable, independently sellable, and easy to start learning on your own. Skilled developers can graduate from college straight into 6-figure salaries, and you could build the skills entirely on your own from your bedroom.

There’s a huge demand for good developers, mostly because so many aren’t that good. If you can work hard at the skill and build your expertise, you can graduate to salaries and opportunities far beyond any of your peers.

Marketing

(Examples: Matthew Barby, Kevin Miller, Cory Ames)

Marketing, if you get good at it, allows you to work in almost any field you might be interested in since every field needs to sell itself to customers. If you want to work in the medical field but not get a medical degree, you can do marketing for a medical technology company. If you want to work in technology but aren’t interesting in programming, you can do marketing at a tech startup.

It’s also, like programming, fairly easy to learn on your own. You can put up your own website in an afternoon and then get to work trying to drive traffic to it. Even if you’re never particularly successful doing it on your own, the lessons you’ll learn in trying to do it and the effort you’ll put into it make you highly attractive to potential employers or mentors.

Design

(Examples: Hannah Phillips, Adil Majid, Tasha Meys)

Design rounds off the 21st century skill trifecta. If you know how to program something, market something, or design something, you’ll be useful in almost any industry you would consider going into. If you want to maximize your options post graduation, getting into one of these three areas will take you a long way.

And design, again, is very learnable on your own. There are online courses, books, challenges that you can work through, you can try re-designing an app or website that you regularly use, you can build your own website and work on designing that. There’s an endless sea of free or nearly free ways to practice it on your own, giving yourself the experience you would need to work in it after graduating.

Sales

(Examples: Scott Britton, Neil Soni)

Tangential to marketing is sales. Marketing helps get a product in front of someone who’s looking for a solution to a problem, sales helps to get a product to someone who doesn’t know they have a problem yet. Sales has always been highly valued, and good salespeople can commission high salaries immediately upon graduating.

The only way to get good at it is to do it. You’ll have to find an internship or side job where you’re regularly trying to sell customers, ideally, one where you’re doing a lot of it at a fast pace, like calling alumni for donations or fundraising for a local charity.

Writing

(Examples: Zak Slayback, Sebastian Marshall, Thomas Frank)

Developing your writing won’t give you the same job opportunities as programming, marketing, or design, but it does open the door for certain aspects of marketing, self-employment through blogging, as well as any journalistic work you might want to pursue. It ends up being important in almost any field you would go into, since you’ll have to regularly and coherently communicate your ideas both in person and over text messages.

How Specialized Should You Be?

Then comes the question of how to specialize in, or combine, these skills you have available to you. One of the core ideas of the traditional, factory-farmed student mentality is that you need to pick one area, say, finance, and get the highest GPA possible in it and ignore everything else.

This is certainly good advice if you want to go down the finance route or other traditional college path, but it doesn’t hold up for being useful or happy in the real world. Over specialization in one area makes you a dull commodity. Someone easily replaced by a higher-performing monkey or a machine. The better solution is what Shane Parrish calls the “Generalized Specialist.”

The Generalized Specialist

The problem with the specialization argument, especially in school, is that it leads to intense, crazy competition where there can only be a few winners. It’s what causes students to become strung out and depressed, and feel like failures despite doing perfectly well at elite colleges.

But by pursuing a more generalized version of your specialty, you can stand out in ways that make you harder to compete with or compare others to. A pure developer is fairly replaceable. A developer who can also do some design work and A/B test landing pages using common marketing tools is much harder to replace.

Specialization gets you off to a good start, but it’s insufficient. You need some diversity to your skill set, which you can do by becoming a generalized specialist:

“A generalizing specialist has a core competency which they know a lot about. At the same time, they are always learning and have a working knowledge of other areas.While a generalist has roughly the same knowledge of multiple areas, a generalizing specialist has one deep area of expertise and a few shallow ones . We have the option of developing a core competency while building a base of interdisciplinary knowledge.” – Farnam Street (emphasis mine)

Everyone I used as an example above was great at one thing, but also good at a few other things that made them much more valuable.

Hannah Phillips is a great artist / designer, and she knows how to do social media marketing to sell her work.

Neil Soni is a great salesman, and he knows enough about beer brewing to start a business in it.

Matthew Barby is a great marketer, and he knows enough about writing and design to create a great site.

None of these people picked just one thing and focused relentlessly on it, they gave themselves the freedom to try out other skills and combine it into their own unique skillset. One that made them more valuable, and gave them more freedom to go after work they were excited about.

In whatever field you’re interested in working in, it pays to ask yourself what other skills go well with it, and then develop your own unique combination of them to give yourself a competitive advantage. Whoever you’re trying to work with has likely seen plenty of great writers, photographers, designers, but how many writers who can market their work, photographers who can also manage event productions, and designers who can also program their own prototypes?

Luckily, the exercise we did at the beginning perfectly sets you up for this. You shouldn’t pick just one of those skills, but rather sample all of them, get some competency in each that you’re interested in, and then go deep on the one that really grabs you.

If you can try out three, four, five skills that are appealing, even for just a month, you’ll get good enough to be able to do some of your own work with that skill to supplement your primary skill. And as those supplementary skills get used in the course of practicing your primary skill, they’ll improve as well.

Getting Started

You now have a roadmap for identifying skills you may want to develop, and a framework for how you might combine them in the future.

All you have to do is:

- Do the exercise at the beginning of this article

- Pick one of the skills you end up with to start trying out

- Start using the sandbox method to develop that skill

If you discover after a month or two that you don’t like that skill very much after all, then no problem! Try something else, and rest assured that the time you already invested is still valuable towards making you a generalizing specialist.

You have plenty of time to experiment, and you don’t have to get it right the first time.