Subconscious Sabotage: Why Friends and Family Clip Your Wings

I showed up for my Freshman year of college interested in starting my own business before I graduated, and then my peers beat a bit of that spirit out of me.

They said that if I wanted to do my own thing or work for myself, I had to go out and do a “real job” first.

I stuck with that idea for two years, diligently working on (useless) skills like resume design and interviewing, preparing for a “real job” so I could get the “experience I needed.”

Then, something hit me.

What if they weren’t giving me advice to help me, but rather to help themselves?

Consider this: You’re talking to someone who has most of their money invested in real estate. You ask them, “Do you think it’s a good idea to invest in real estate?”

Obviously, they’ll say yes. For them to say “no” they would be admitting that they’d made some mistake in putting all of their money there.

Or, what if they didn’t advise you to invest in real estate, you invested elsewhere (say, Tesla stock), and you made significantly more money than them? They’d feel even worse because they’d know that they could have had that same success, but didn’t.

Another example. Whatever your bad habit or quality is, go tell someone close to you with that same quality that you’re going to fix it.

If you sleep less than 8 hours, tell your insomniac friends that you’re going to start going to bed at midnight.

If you’re overweight, tell a fat friend that you’re going on a diet.

If you drink daily, tell your alcoholic buddies that you’re stopping.

Suggest doing the most against-the-norm thing to your social circle.

You’ll get responses like “oh, haha, good luck,” or “yeah, okay, we’ll see how this goes,” or more subtle ones like “hey good for you!” followed by teasing when someone else orders a Cinnabon / coffee / drink: “make sure you don’t let John have any!”

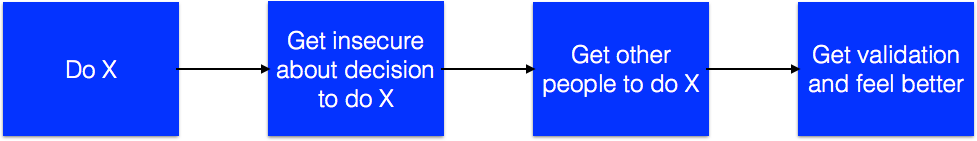

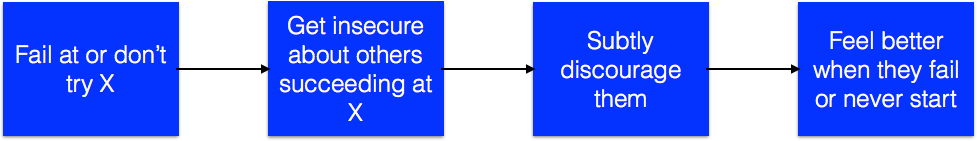

What’s going on? It’s not that your friends consciously want you to fail, it’s that if you succeed, that means that they have no excuse for not fixing their faults. It’s easy to be fat and say “oh I can’t lose weight” until your best-fat-friend loses a ton and proves you wrong.

Out of self-preservation and laziness, your friends and family don’t want you to succeed too much. They want you to succeed enough to be happy, but not so much that you make them question themselves.

Put In Your Time

This leads to one of the most insidious versions of this subconscious sabotage:

“You have to “put in your time” before you get to have a fun life.”

Here’s why it’s nonsense. There’s no universal law that you have to “put in time” before you have a fun life or job. It’s just what most people do.

Consider where you heard this advice. Odds are it came from your parents growing up, and from your peers who heard it from their parents. If you drill down on why you believe it, you’ll eventually arrive at “because X said so.”

Is it possible that, just like the fat friend saboteur, your parents and peers don’t give you that advice to help you, but to make themselves feel better?

Imagine you spend 20 years working a job you hate. Then, some smart kid comes along and says “hey I’m going to do something fun when I graduate.” If you spent 20 years being miserable, how are you going to feel if she pulls it off? Jealous! Angry! Regretful! If this kid could pull it off and skip straight to that fun life you’ve been “putting in time” for, then that means you wasted 20 years.

The solution? Tell her it’s not an option. Convince her that she has to “put in the time” to have a fun life, so you feel better about your decisions and the years wasted.

It’s not conscious, and I’m not saying that your parents and friends are evil and out to get you. They think they’re doing you a favor and keeping you safe, but at root, it’s just their own insecurities or fears.

They believe this advice themselves and never questioned it, so you have to do the questioning for them.

Recognizing the Bad Advice

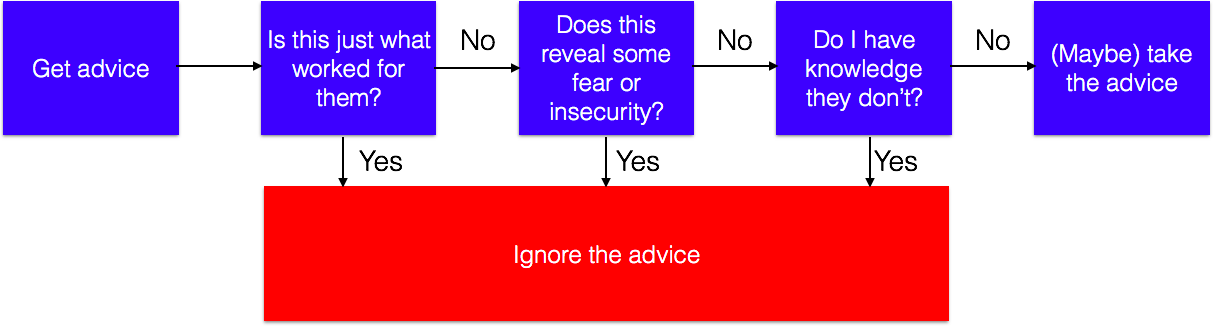

Whenever someone gives you advice, you have to carefully consider whether they’re saying it to help you, or to reaffirm a choice they made.

When you start listening for this kind of advice, you’ll see it everywhere. Most advice is to re-affirm the advice-giver’s beliefs, and not to help you. You can only fully trust advice when it does not support the giver’s decisions. Otherwise, you have to weigh it for what truth might be in it, get more data, and form your own opinions.

Here are some common forms of bad advice:

- You should do X as a career (especially common from parents who think there’s only a few paths to security)

- You should study X (reaffirming what they studied, or what they wish they studied)

- You should do X diet (usually the diet the advice giver is on, or pretending to be on)

- You won’t be able to do that because X (reaffirming their own fears of failure)

- You should stop doing X (reaffirming their own, usually temporary, abstinence)

- X is really hard (they couldn’t / can’t do X)

- You can’t make money doing X (they don’t know how to make money doing X, or they’ll be jealous if you make money doing X)

Advice is bad if:

- It’s overly narrow (X career instead of find one you like)

- The giver is over-invested in a position (their own diet vs the best diet)

- They have no experience (“you can’t make money writing” from a non-writer)

“That only worked for them because X”

I want to call out another particularly bad version of sabotage, the “that worked for them because X” argument.

If you’re telling someone that you want to work for yourself, lose weight, travel the world, breed Pomeranians, and then point to someone else that you know that did it successfully, whoever you’re talking to might bring up a point like this:

- Well he could do that because he went to a really good school

- She was born good at painting

- He’s Asian

- She had rich parents that she could fall back on

- He’s just special

It might sound like they’re bringing up a good point, but they’re focusing on a minuscule disadvantage that ignores the greater picture. You have a mix of advantages and disadvantages, and them saying “I don’t think you’re as good as them because X” is not helpful advice.

It’s them assuming that you’re both stuck a certain way, which simply isn’t the case. And it’s worth noting that simply knowing someone who did what you want to do is a massive advantage. They might not have had the same kind of person to lean on.

Is the Advice Giver Qualified?

You also have to consider what qualifies anyone to give you advice.

Tell your doctor parents that you have a friend who travels the world running a fashion blog and you’re going to learn how to do it, and any argument they make against your plan is moot because they don’t know anything about running a travel blog.

They are only qualified to give you advice on doctoring, not on whether you’re qualified for travel blogging.

The same goes for your friends. They might say something is hard, impossible, you’re not ready, but they’re just making up disqualifications to reassure themselves, or to explain their gut impulse.

They probably thought “that doesn’t sound like it’ll work,” then made up reasons to explain that reaction to themselves. Always ignore advice from unqualified parties.

A Note on Fear

With parents, much of the work advice comes from fear. They don’t necessarily think that you can’t work for yourself, but they’re not sure you can pull it off, and they don’t want to fear for your ability to support yourself.

It’s nice, but it’s also selfish. What they’re saying (usually not meaning it this way) is “I don’t believe in you” and “I don’t want to be worried about you,” assuming that you can’t do it and that you won’t be worried enough about yourself.

Handling and Avoiding the Bad Advice

Whenever someone starts giving you advice, check it based on the criteria above. If there’s any way to interpret that advice as them being self-serving, or it being unfounded, you have to ignore it.

Ask yourself:

- Could they be saying this to feel better about a life choice they made?

- Could they be saying this out of their own insecurity?

- Could they be saying this because if I succeed, it means they failed?

- Could they be saying this simply out of naïvety and inexperience?

- Do I have any knowledge they don’t, that makes their advice invalid?

- Could they be saying this out of fear?

When the answer to any of these is “yes,” don’t challenge them on it (unless you’re a pain in the ass like me). Most people aren’t doing it deliberately, they legitimately think they’re being helpful, so just nod and smile and thank them.

Then, of course, promptly forget whatever they said.