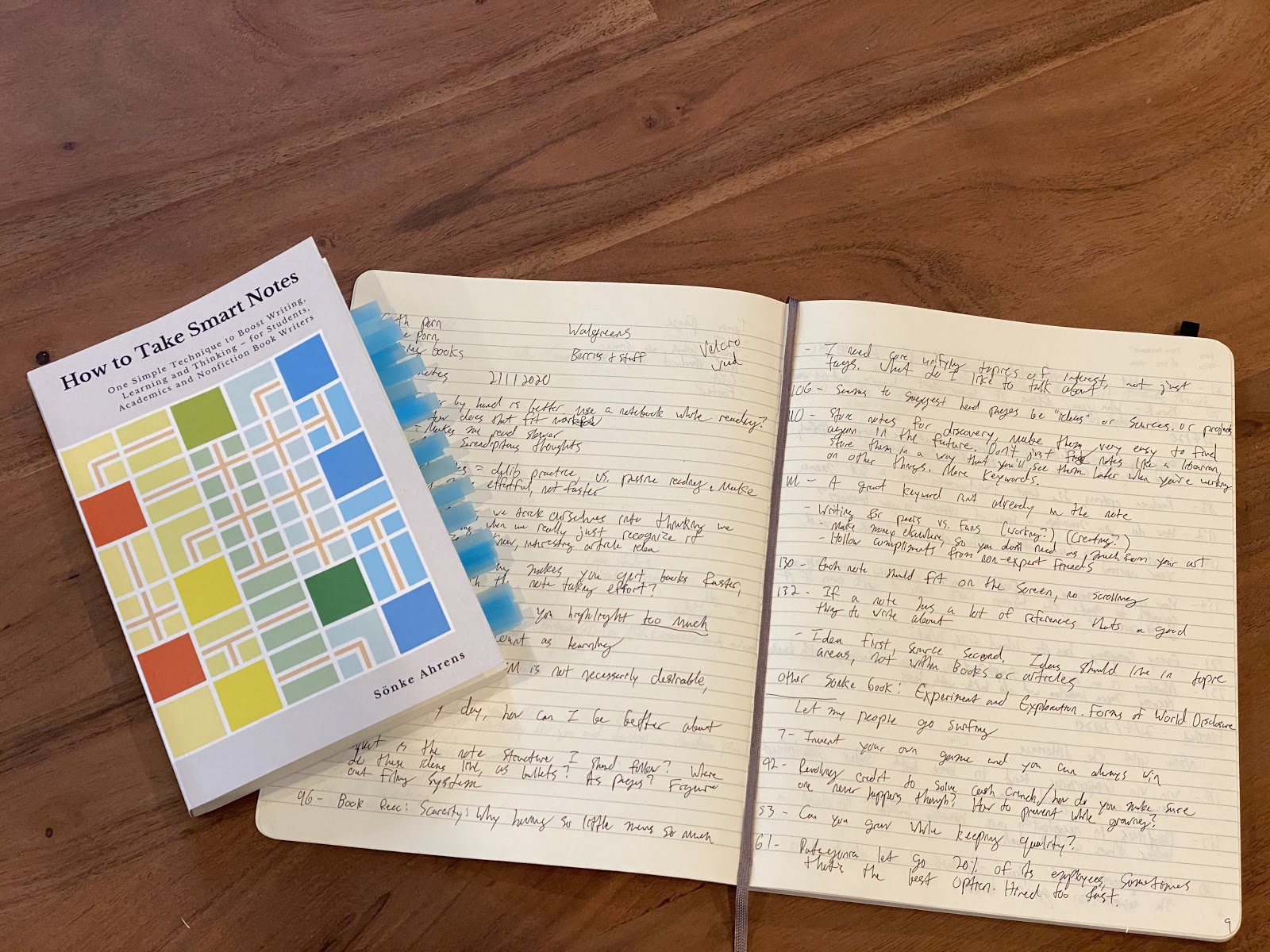

How to Take Smart Notes: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Take Smart Notes is a book by Sonke Ahrens explaining the "Zettlekasten" methodology developed by Niklas Luhmann, a 20th century Sociologist who published a prodigious amount of work: 70 books and more than 400 articles before his death.

According to interviews with Luhmann, work was "effortless" for him because of the system he'd developed for taking, and utilizing notes on everything he'd read and thought. Many writers and researchers have attempted to describe how other people can replicate this system themselves, but according to Sonke, they miss the mark.

How to Take Smart Notes aims to provide the most accurate presentation of the "Zettlekasten" system Luhmann developed, and regardless of the accuracy, it is a phenomenal system for getting more out of what you read.

The core idea of Smart Notes is that purely extracting highlights is generally a waste of time. A highlight speaks to you when you take it, but if you don't capture the idea that the highlight gave you, you're unlikely to remember the importance of that highlight later. Or even if you do feel some spark when revisiting the highlight, it might be a different interpretation.

If you've ever looked back at your book highlights and thought to yourself, "why did I highlight this?" then you know what problem we're solving here. And if you don't already take book highlights, even better! You're going to dramatically level up your reading comprehension and retention.

Instead of simply highlighting passages, the Smart Notes system encourages you to manually create notes of the ideas you get as you read.

...the mere copying of quotes almost always changes their meaning by stripping them out of context, even though the words aren't changed. This is a common beginner mistake, which can only lead to a patchwork of ideas, but never a coherent thought. (Page 75)

You want to create notes that are relevant to contexts important to you, not just related to the book you read.

Since reading How to Take Smart Notes I've been adopting the Zettlekasten method in my own reading, and I can see how it's improving on an already strong note-taking process. By adding my own contextual notes to my highlights, and taking time after finishing a book to process and better organize those notes, I'm able to generate more ideas as I read and put those ideas to better use.

Here I'll share how I'm applying the Smart Notes system in my own work, through my interpretation and adaptation of the method Ahrens lays out in the book. It is not a perfect application: I've adjusted a few things based on what makes sense to me, so I'd encourage you to read the book as well.

Also, this method works best in my new favorite tool Roam, so if you haven't started using it I'd encourage reading my article on Roam or checking out my course on it.

Alright, let's start taking Smart Notes.

Step 1: Take Physical Notes as You Read

When you're reading a book, have something you can physically take notes on with you at all times. You can do this for articles, too, but I'm going to focus on books.

I'm currently using two notebooks for this: a large Moleskine I carry with my laptop to use 90% of the time, and a small Field Notes notebook I keep in my pocket for notes on the go.

But why physical notes? When you have to write your notes by hand, you'll be a bit more thoughtful with them and be forced to put things in your own words. With typing, it's easier to just re-type what you're reading (or worse, copy & paste), and not capture the whole context of the idea.

You also remember things better when you write them out by hand. Ahrens tells a good story about a study done on University students, which found that students who took lecture notes by hand remembered them much better than students who took notes on their laptops:

Handwriting makes pure copying impossible, but instead facilitates the translation of what is said (or written) into one's own words. The students who typed into their laptops were much quicker, which enabled them to copy the lecture more closely but circumvented actual understanding. They focused on completeness. Verbatim notes can be taken with almost no thinking, as if the words are taking a short cut from the ear to the hand, bypassing the brain. (Page 78)

As you're reading, write down anything that comes to mind from the book and where you found it. It could be your own interpretation of a passage, or it could be some other seemingly random idea that the book sparked. Capture it in your notebook as a quick "fleeting note" that you can expand on later.

Keep it very short, be extremely selective, and use your own words. Be extra selective with quotes don't copy them to skip the step of really understanding what they mean. (Page 24)

Step 2: Have a way of recording bibliographical sources as you read

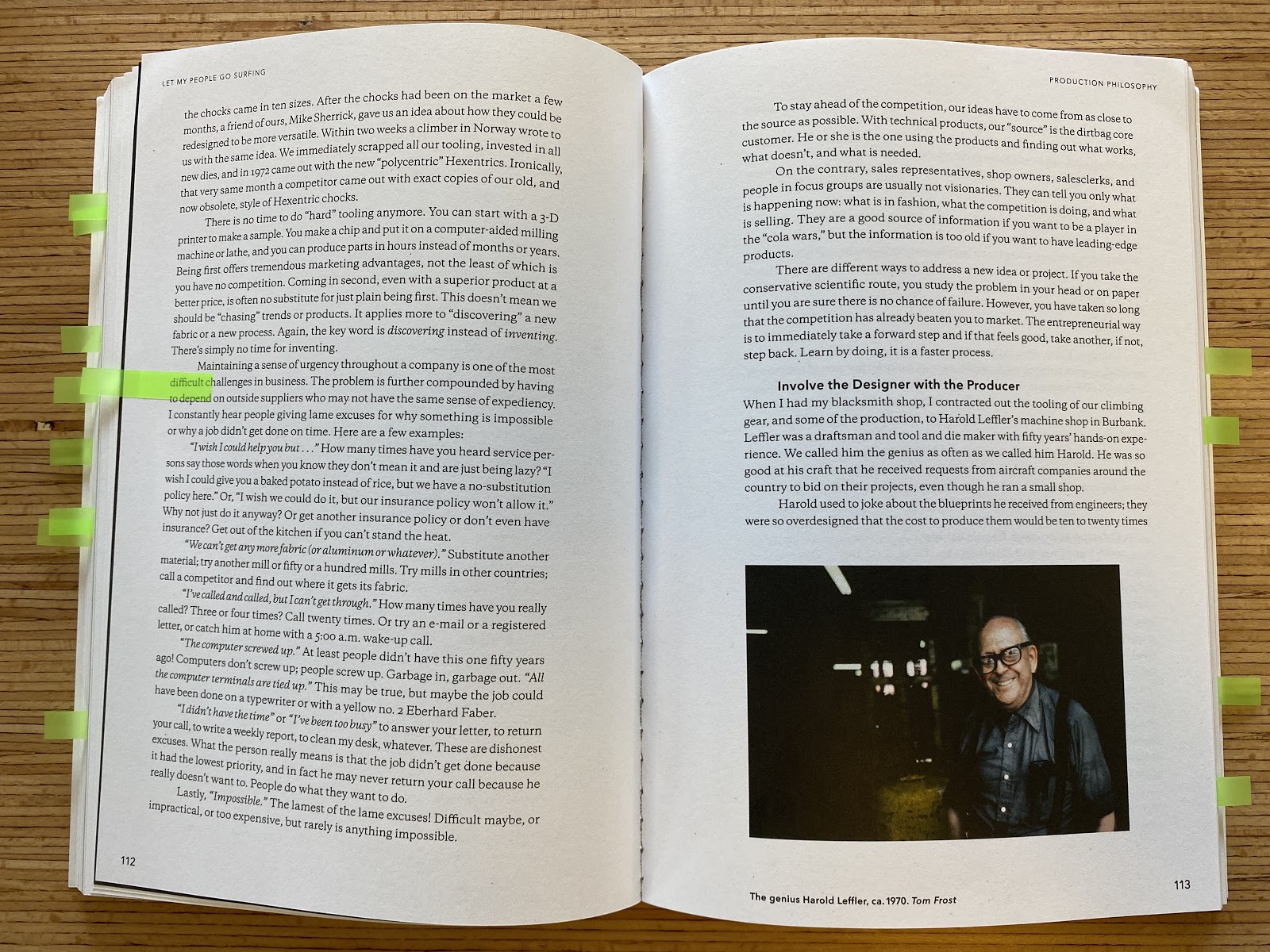

This is where I deviate from Ahren's method slightly: I capture both my notes and the highlights, because I like having direct passages to quote later in articles like these. I write the page number in my notebook so I know where the idea came from, and I sticky tab that section in the book so I can pull out the quotation later.

But as a rule, only tab a section if it inspired you to write an idea down in your notebook. Then mark the idea with the page number you got it from, and leave a sticky tab in the book. Don't be tempted to mark things that "seem" important, only save the ones that speak to you.

If you're on Kindle, you can use the highlight feature to accomplish the same thing. Though I find the Smart Notes method lends itself nicely to rediscovering physical books.

Again, not technically part of the Smart Notes methodology, but if you're like me and enjoy having specific highlights as references later, this is a nice addition.

Step 3: Upload your notes

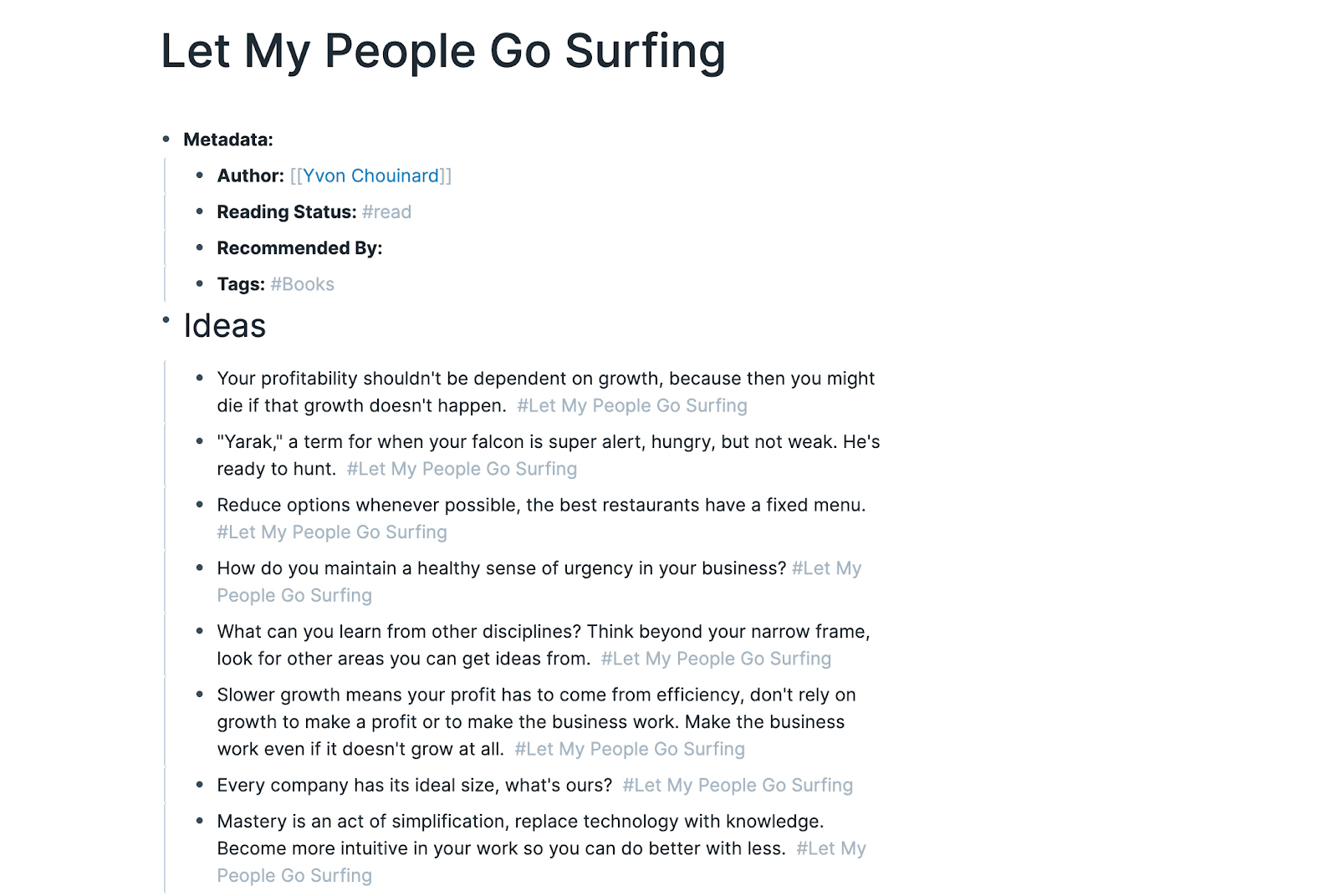

Once I finish a book, I'll upload all of my notes from it to Roam.

There are two kinds of notes to upload:

References , the highlights that I got ideas from and want to extract

Ideas , the thoughts that I had while reading the book

For the References, I'll use Readwise to scan them in from the physical book or export them from Kindle.

For the Ideas, I'll re-type them from my notebook and expand on them to make them into coherent thoughts. I'll start by just listing all of these out under an "Ideas" heading, but this is temporary.

The important question here is: how can I make this idea detailed enough to stand on its own, without the context of the book or the associated highlight? You want each of these ideas to be fully formed thoughts that you can reference in a bunch of different areas later.

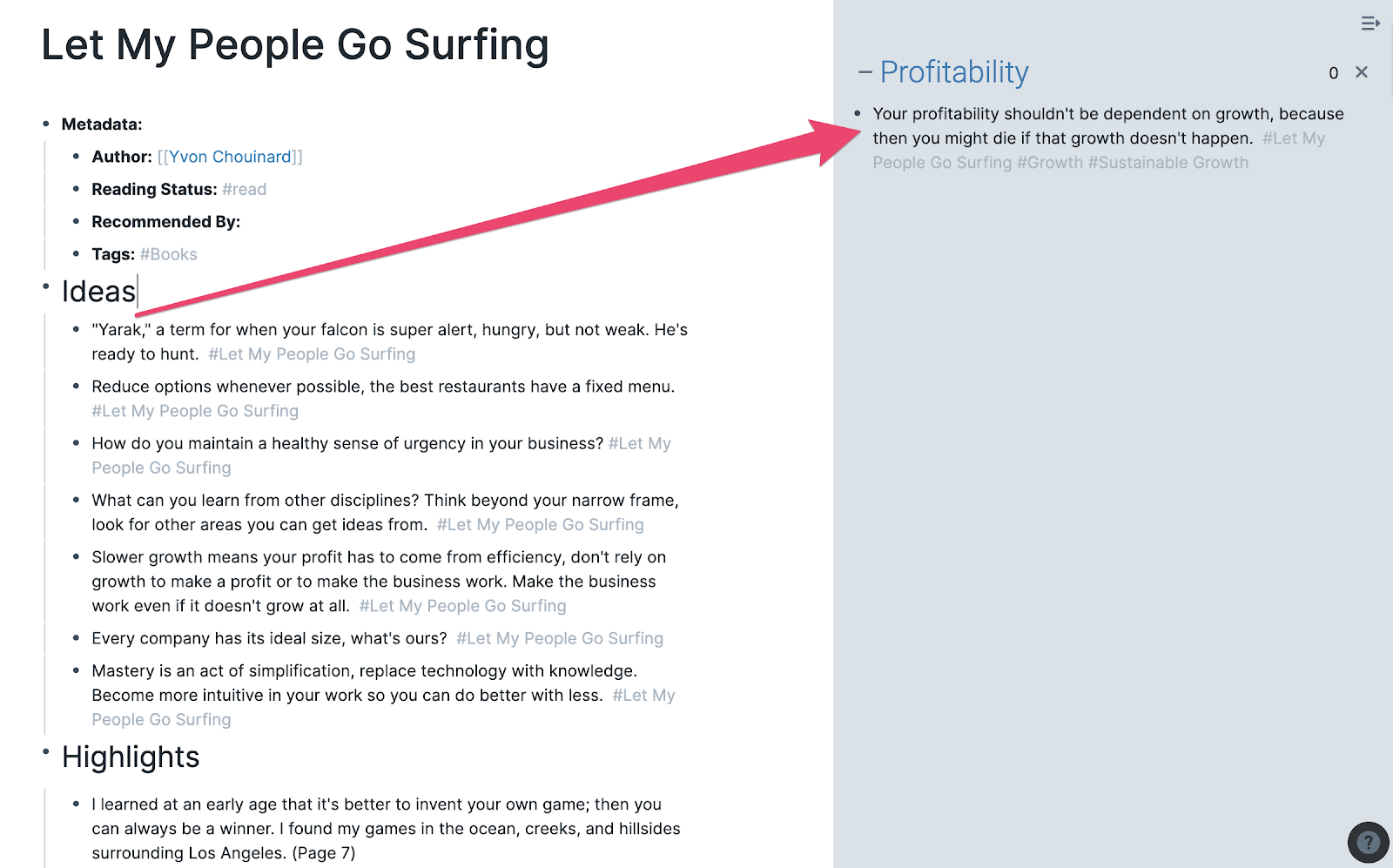

Step 4: File Your Notes

One of the core ideas of Smart Notes is to file information based on the context you want to rediscover it in, not based on the context you found it in.

In the old system, the question is: Under which topic do I store this note? In the new system, the question is: In which context will I want to stumble on it again? (Page 40)

Leaving the ideas the book or article inspired within the book makes them much harder to find later. For example, if I wanted to write an article in the future on creating urgency, I might not remember that it was a topic in Let My People Go Surfing.

Tagging the idea with its relevant contexts helps, but by moving an idea to its primary context you can better organize it within that context by nesting it under other topics or headings.

So the last step with each of your Smart Notes is to move them to where you most want to re-discover them, and to add any additional contexts you think could be relevant in the future.

First, I'll tag each idea with the book I got it from. This just makes sure that once I move it, I'll know where it originally came from.

Then I'll go through each idea and decide what existing or new topic area within my database it's most relevant to. For example that first bullet on profitability makes the most sense to live in the "Profitability" note.

I also added tags for "Growth" and "Sustainable Growth" since I might want to remember this idea in those contexts as well.

Step 5: Use and Organize Your Notes

As you develop more notes within a certain idea, you'll be able to start organizing those notes into bigger ideas, or even full deliverables like articles.

This is the true power of the Smart Notes system: since you're constantly capturing the ideas that you're getting from disparate sources and organizing them in their most important contexts, you can quickly develop ideas for new articles, books, scripts, whatever it is you create from your ideas.

And since each idea can be referenced from multiple places, you can use it to help advance and organize your thinking in many places at once.

All you need to do to turn your ideas into new articles or other works is start organizing and expanding on them. Since implementing this method, I've been impressed by how effortlessly it allows new ideas to flow. Even a few ideas from a couple books dropped into a topic form a jumping off point for a bunch of other ideas, and make it easier to get past writer's block.

In Summary

-

Grab your own copy of How to Take Smart Notes

-

Get a good notebook for taking notes as you read

-

Handwrite ideas as you have them while reading, and reference where they came from

-

Upload your highlights and ideas once you finish a book

-

File those ideas in their most useful contexts

-

Use those ideas to create new works!