Your Brain on Nitrogen

I pointed to the shoddily written number 20 and looked up at the instructor. He showed me the stopwatch. It read 44 seconds.

“44 seconds? How is that possible? My time on the surface was 22 seconds. Why would it take me twice as long down here?” I blew a small trail of bubbles. My instructor gave me an understanding nod, and pointed towards the surface. He’d been anticipating the confusion, but I’d have to wait until we were above water for an explanation. 120 feet underwater, covered in SCUBA gear, the only person you can talk to is yourself.

The deeper underwater you go while SCUBA diving, the less time you can spend there. You start to breathe in dangerous levels of nitrogen, and you use up your air supply much quicker. You’re safe spending an hour at 30 feet underwater, but beyond 80 feet you have less than 15 minutes. A typical SCUBA excursion doesn’t go much below 80 feet.

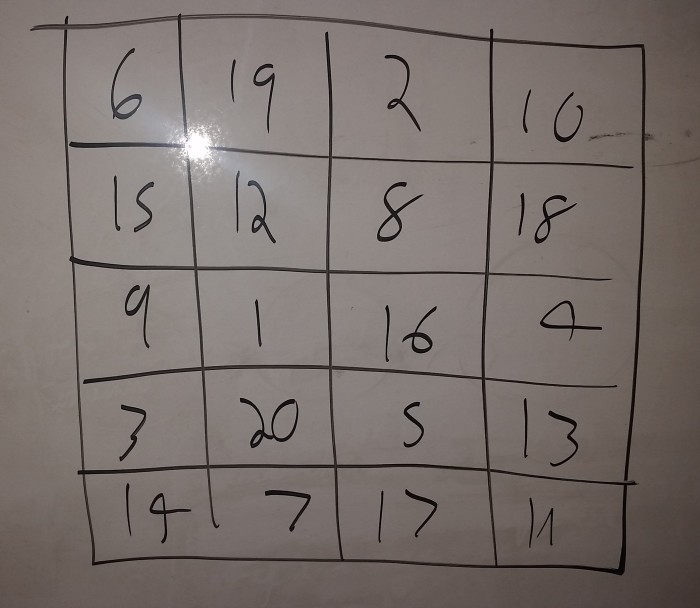

This wasn’t a typical SCUBA dive. It was a “deep diver” training course where a divemaster takes you down 120 feet to show you how it affects your body, to make you more aware of those dangers in the future. Before the dive, you test your mental agility on the surface with a board like this:

You have to connect the numbers 1 to 20 as quickly as possible while the instructor times you. Then you do the same test at 120 feet to see how your times compare. As I’d just learned, being down that deep cuts your brain’s speed in half. That’s not the scary part though.

The scary part is that despite operating at half speed, you feel exactly the same.

Your Brain on Nitrogen

Why does deep diving make you stupid? Sitting or standing where you are right now you’re in 1 “atmospheric unit” of air pressure, or 1 AU. That’s the amount of oxygen, nitrogen, and everything else that you’ve been used to breathing for your entire life. If you go high enough above sea level you can get to air pressures below 1 AU (great for cardiovascular training and saving money on alcohol), but when you go underwater you very quickly reach pressures above 1 AU.

Every 33 feet deeper you go, the pressure on you increases by 1 AU. At 33 feet you’re breathing in air at 2 AUs, so you’re getting twice as much oxygen and twice as much nitrogen in a given volume of air (since the pressure is doubled). At 66ft you’re getting triple, at 100 you’re getting quadruple, and so at 120 you’re breathing in almost quintuple the normal amount of air.

You don’t notice it though. Breathing feels the same whether it’s 1 AU or 3 AUs since your lungs are expanding and contracting the same amount. It only becomes a problem when you want to surface. If you take in a breath at 3 AUs, and then hold it all the way up to the surface, you now have three times your lung capacity worth of air in your lungs. They’ll either explode or force all of the excess nitrogen into your blood stream. The sickness from that much nitrogen being forced into your bloodstream is called decompression sickness or the “bends.” When you hear about the dangers of SCUBA diving, the bends is what people are usually talking about.

The bends is easy to avoid though. You just have to go up slowly (no faster than 1ft/sec) and remember to breathe normally. What’s not avoidable is the fact that at 120 feet you’re breathing in almost five times your normal amount of nitrogen… and nitrogen gets you high. It’s not a munchies and petting the carpet high, but rather a subtle mental hindering where, as I learned in the story at the beginning, you’re operating at a fraction of your normal speed. In particularly bad cases it can present itself as “nitrogen narcosis.” Someone who’s “narc’d” is visibly high on nitrogen, and they behave a lot like a drunk person. It’s rare though, and tends to only happen when you’re unhealthy, underweight, haven’t slept, or drank alcohol before diving.

Before taking the mental agility test at depth, if you had asked me how I felt, I would have said perfectly fine. I had no indication that I was operating slower than usual. Which raises the question: is that exclusive to nitrogen and SCUBA diving, or does it happen in other areas of life as well? Are there other areas where, despite thinking we’re on the surface, we’re actually 120 feet underwater?

Sleep Deprivation and the Brain

“I only need 6 hours of sleep”

“Don’t most people need 8 hours?”

“Yeah, but I only get 6. I’m still getting my work done and I feel fine.”

There’s no scientific evidence of non-mutant humans being fully functional on six or fewer hours of sleep. There is, however, plenty of evidence that we need anywhere from 6.5-8 hours, with most people falling in the 7-7.5 range [1][2][3]. Despite the evidence, 40% of adults are sleeping fewer than 7 hours a night, and 46% of people age 18-29 are sleeping 6 hours or fewer.

There are plenty of (bad) reasons for sleeping only 6 hours: work, school, stress, House of Cards marathons.

But I think there’s one main reason it doesn’t stop: “feeling fine.” If you stay up a few hours later, only get 6 hours of sleep, and then go through your day yawning a bit more but still feeling functional, it’s enticing to say to yourself “well… I could get two more hours a day if I did this every night!”

Sleep deprived people are actually capable of producing work at a level equal to non-sleep-deprived people. Their intellect is about the same, as is their ability to solve basic problems. What sleep deprivation screws up is our ability to focus. When we’re sleep deprived we’re extremely susceptible to distraction, and when we get distracted, we find it more difficult than usual to get back on task [4]. Despite being so distractible, we don’t notice our mental inattention, and assume we’re operating normally [5]. Worse, we’re not remembering nearly as much as we normally would, and in extreme cases where young adults were kept up for 36 hours they had the same mental agility as an average senior citizen [6][7].

Feeling fine on 6 hours of sleep is the same as feeling fine at 120 feet underwater. You’re functioning, and you don’t have any clear indicator that you’re not functioning optimally, so unless you have a mental agility benchmark to compare against you have no reason to believe you’re brain is trudging through molasses.

The problem magnifies after weeks and months of maintaining a habit of sleep deprivation. If you’ve been used to 8 hours a night, and then you only get 6 for one night, you’re more sensitive to the effects. Your mind feels slower, you can’t focus as well, you forget things, and you feel generally out of it. But as you under-sleep more frequently you lose that point of comparison. As 6 hours becomes the norm you start to redefine what “fine” feels like, despite it being an objectively worse state.

Feeling Fine

Feeling fine is more dangerous than feeling bad. When we feel bad, we know there’s a problem, and we can usually point to where the problem is coming from. We can say “well, my leg really hurts, so I should probably get a doctor to stitch up this bullet hole.” But if we’re used to operating sub-optimally, we have no wound to point to. We have no clear weakness or indication that we’re not functioning how we should be.

Without a sense of “something is wrong here” we lack the motivation to seek out change, even though experimenting with certain changes can lead to huge results. We’ve all experienced an “aha!” moment where something suddenly “clicks.” A moment when we realize something that we didn’t know before, that we didn’t know we didn’t know , and that makes our lives better. It could be as simple as someone telling you that you can type “Timer 20 minutes” into Google to start a 20 minute timer, or someone showing you that you can deposit checks from your phone. They’re small and simple things that make your life better, but you don’t know that you don’t know them so you don’t seek them out.

Then there are the much bigger changes. I’ve already harped on sleep enough, so here are some others:

Meditation. This one is tricky because if you’re doing it wrong, you could try it for a year, have no results, and give up out of frustration. That’s what happened to me when I first tried. But when you do it properly, you eventually reach a state of self-observation where you can see how manic and crazy your mind is. Once you have that observation you begin to tame your mind, and as you do, you experience significant boosts to impulse control, focus, contentment, and calmness. Without having experienced it it’s impossible to know what you’re missing out on.

Exercise. The most obvious one on the list, it can’t go unmentioned. Exercise improves your focus, energy, happiness, sleep, skin, heart health, physique… assuming you’re doing it properly. If you exercise by sitting on an exercise bike for 20 minutes at the lowest setting watching the food channel and not breaking a sweat you’re doing it wrong. That could even be worse than not exercising at all because you’re tricking yourself into thinking that you are. But if you’re truly pushing your body to failure on a regular basis, you’ll develop a much better sense of what you’re capable of, what it actually means to be tired, and you’ll start feeling the benefits immediately.

Learning. The centenarian study analyzed a cohort of people living around the world who were over 100 and still fully functioning (walking around, mentally aware, etc.). Diet, lifestyle, and genetics played a big part (eat Mediterranean style, don’t stop moving, have healthy parents), but another significant commonality among them was a dedication to learning.

They retired from work but never retired their minds–they kept seeking out new things to learn whether it was dance, art, language, literature, and never let themselves simply become the pure “consumers” that their less-well-preserved peers became. Challenging yourself by learning new things, whether it’s taking a week to learn basic juggling or a year to learn Mandarin, keeps your mind agile and helps you see surprising relationships between different areas of life.

Hydration. My roommate in high school drank an absurd amount of water. One day he bought so many bottles of water that he stacked 24-packs of Poland Spring up to the ceiling. I would make fun of him for how much water he was drinking. One day I asked why and he simply said “try it, you’re probably dehydrated.” So I did, and he was right. I didn’t know it but I had been dehydrated for much of my life and it was affecting my sleep, skin, energy, sense of well-being, and hunger. I’ve suggested the same experiment to a number of people and they usually report similar results.

Sunlight/Vitamin D. If you live above the Tropic of Cancer (see picture on the right) there’s not enough sunlight in the Fall, Winter, and Spring to provide the Vitamin D your body needs. Since the sun is diffused by its angle to your location, you aren’t getting the UVB radiation your skin needs to spark Vitamin D production. Without sufficient Vitamin D you sleep worse, have less energy, retain less lean muscle mass, and can develop a form of depression referred to as “Seasonal Affective Disorder,” or SAD (very clever). And before you ask, yes, putting UV-B blocking sunscreen on every day might make you depressed.

Vitamins and Minerals in General. Get a blood panel done, as comprehensive of one as you can afford (or that you can convince your doctor to bill to your insurance). Odds are that you’re deficient in something you might never have thought of (how high is your Chloride?) and fixing that imbalance will lead to a host of benefits to your health and well being. I recently found out I’m overdosing on magnesium… there’s no way I could have guessed that on my own.

Caffeine. I haven’t had coffee in a bit over a year. I used to have anywhere from two to five cups of it a day, but I cut it out just for the sake of experimentation. I’m confident that caffeine in more than small doses is a bad bet. It spikes your mental activity briefly, but then you go into a slump afterwards that you don’t normally notice (which is why so many people say “oh I don’t crash from coffee”). One or two cups of coffee in the morning is fine; it’s the 5 cup-a-day or redbull chugging caffeine addicts that need to be worried.

Naturally there are hundreds of others, and tinkering with our lifestyle is the only way to find these things. Most of us will go through life assuming we’re in the boat up on the surface: we’re fully functioning, there’s no reason to change anything, no reason to mess with the status quo. But what if we’re wrong?

What if, for everything changeable in our lives, instead of assuming we’re on the surface, we assume we’re 120 feet underwater?