Option not Obligation: How to Beat the Sunk Cost Fallacy

I’m writing this from a standing table in the Air France lounge of the Charles de Gaulle airport. The moment you enter this particular lounge, you’re greeted by a buffet table of red wine, champagne, aperol, and other aperitifs to enjoy while waiting for your flight.

The remnant college student in me can’t help but feel a tad blessed in the presence of free alcohol, and it seems I’m not alone. Most travelers, as soon as they enter, pour a glass of wine or liquor and sink into the arm chairs lining the wall of the lounge.

This is not to judge any of their reactions. Alcohol at 3pm during a football match is one of the best times for it, but I’m curious about why everyone pours a drink in the first place. Is it because the entirety of this lounge is typically predisposed to drinking wine at 3pm on a Sunday? Or is there something else at play causing us to indulge in a way we wouldn’t outside of this environment?

If we took everyone in the lounge and put them in the middle of a food court, how many of them would go to a bar? Given the opportunity to spend money on alcohol, would they still want it?

My suspicion is they wouldn’t, and the main reason they’re having it here is that they paid to enter the lounge (either at the entrance or by purchasing their ticket), and now that they’ve spent that money they feel obligated __ to get some of their money’s worth in alcohol.

The tendency to feel like once we’ve spent money (or any resource) on something we must earn back our investment impacts our decision-making in all walks of life. And, sadly, it can lead to significant losses of time, money, health, and happiness.

Here’s why.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy drives this desire to “make the most” of our spent resources, but to understand the sunk cost fallacy, we first need to understand sunk costs.

The idea of sunk costs originates from business accounting, meaning “ any cost that has already been incurred and can’t be recovered.” In microeconomic theory, future decisions of the business should only be based on future costs, that is, costs that are not sunk.

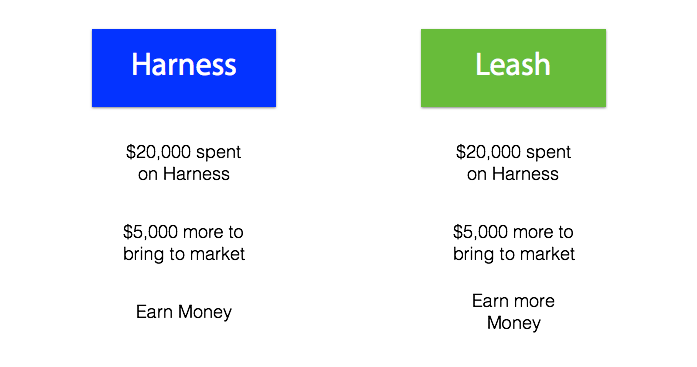

To visualize this, say a fictional company of yours is planning on launching one of two separate products to enhance the poodle walking experience. One is a lovely harness that keeps poodles cool and comfortable while walking, the other is an ergonomic leash with finger grooves for your holding pleasure.

Both products, from this point, will cost $5,000 to bring to market, but the leash is expected to make slightly more money over the same time period. So you’d make the leash, right?

What if I told you that you’d already invested $20,000 into the harness, and had been working on it for a year. Someone just showed up today with the leash plans and wants to put the money towards that instead.

Now, which would you make? Assuming no other variables, the economically rational decision is still to __ make the leash, even though you already spent $20,000 and a year on the harness.

This is hard to accept. We want to say that, no, the harness is the smarter decision, but there’s no economic justification for that reasoning. Sure we put a lot of time into it, but if the goal is to make money then at any given point we need to do the thing that will result in the most money. And in this case, that’s the leash.

If you don’t believe me, here’s a visual comparing the two choices. In choice A, we have to make the harness, which has $20,000 spent, $5,000 more to be spent, and then “money” as a result.

In choice B, we still have the $20,000 spent since we can’t get that back, we have the $5,000 more to be spent, but we have “slightly more money” instead. Obviously choice B is better.

Again, yes, this is extremely reductionist and there would be more variables but it serves to illustrate the point.

That pull you felt towards option A, knowing what we’d invested in it, is what’s called the sunk cost fallacy. It’s our tendency to make decisions based on sunk costs, even though those sunk costs are going to factor into whatever choice we make (since we can’t get them back). The $20,000 invested is going to have been spent no matter what, so the decision you make should ignore that the money is gone.

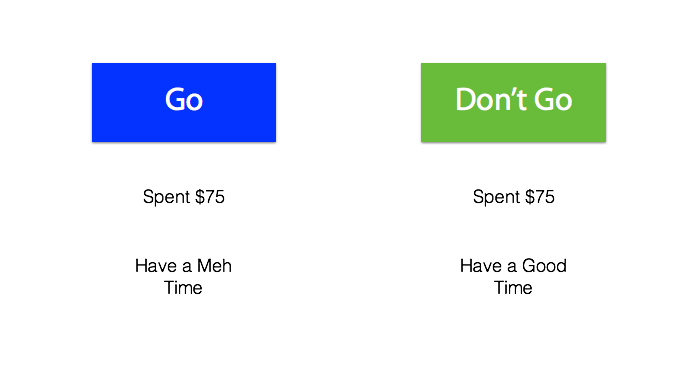

Here’s a classic example from your personal life. Say you spent $75 on tickets to a basketball game, ballet, rodeo, whatever you enjoy. Now say it’s the night of the event, you feel pretty tired, don’t want to go out, and aren’t at all excited about still going.

Would you, or should you, still go?

Most people will say yes, and even if they say no their actions typically align with yes. Even though they’re not excited about going to the game anymore, they still go, just because they spent money on it.

But this doesn’t make sense for the same reason making the harness doesn’t make sense.

In option A, you have the cost of “spent $75” and the outcome of “feel meh at the event.” In option B, you have “spent $75” and the outcome of “feel happy and relaxed at home.”

With the costs being equal, and the option B outcome being significantly better, the obvious logical choice is option B, but so few people make this choice.

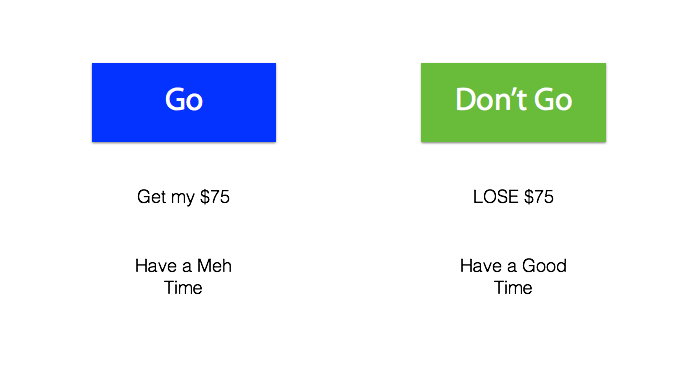

Instead, they succumb to the sunk cost fallacy and end up wasting their time, money, and energy on things they shouldn’t. They think more like this:

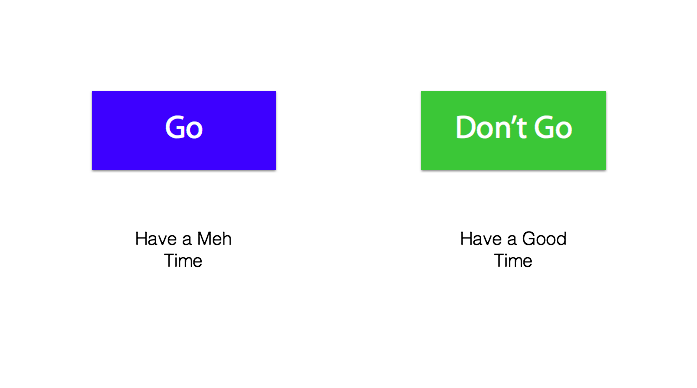

They ignore that, whatever they choose, that $75 is gone. The most accurate portrayal is actually this:

Even when we understand this logically, we still tend to make the mistake. And that’s where the dangers of the sunk cost fallacy start to creep in.

Dangers of the Sunk Cost Fallacy

6 years ago I made a friend who, at the time, I thought was a successful entrepreneur. He was living in NYC running his company of 8 people and seemed enthusiastic about the progress they were making and how well it was doing. They’d raised money, had their product out, and he was animated talking about it.

A year ago, he messaged me on Facebook asking if I was interested in joining a new company he was starting. My immediate question was: what happened to the last one?

It became clear that the company had never been doing that well in the first place. He had a small and stagnant user base, and while trying to grow it, he burned all of his investors’ money. Then, he started investing his savings into the company, being confident that it would “take off eventually.” His savings dwindled, his wife left him with the kids, and the company folded.

If he’d been able to look at his company soberly, he would have recognized that it was time to let it go years ago. Even if he couldn’t save his investors their money, he could have at least protected his own assets. But blinded by the amount of time he’d sunk into it, he kept throwing good money after bad and ended up losing much more than he would have if he had cut his losses.

That’s an extreme case, yes, but we all have stories like this from our lives. The friend who won’t leave a relationship because they “have so much history together,” another who keeps repairing a long-dead car, another who hates their job but can’t leave because they’ve “been doing it for so long.”

If we remain blind to the dangers of the sunk cost fallacy, our losses quickly multiply. In moments of financial, emotional, or temporal loss, we double down and lose more, thinking that we’re somehow going to get back what’s already gone.

But we don’t need to. After starting to recognize the sunk cost fallacy’s effects in my own life, I developed a mental model that anyone can use to avoid it.

Option, not Obligation

The sunk cost fallacy impacts our decisions by making us feel like because we’ve spent money on something, we’re obligated to take advantage of what we received for our money.

The trick to beating the fallacy is to look at investments as giving you options, not obligations.

From the story at the start, by being in the lounge surrounded by booze I had the option to get blasted on Campari, but I didn’t have the obligation to. Being there didn’t mean that I had to take full advantage of it, even though it’s tempting to feel like I’m losing money if I don’t.

When traveling, people tend to feel obligated to see every single sight (whether or not they care about art history, animals, landscapes, or architecture), and end up burned out and frustrated wondering why they didn’t enjoy their vacation. But if they had treated the location as giving them the option to see these things, they would have made better choices than waiting 3 hours in line for an Instagram of the Mona Lisa.

This model, thinking in options, not obligations, applies in any domain where you make a financial, emotional, or temporal investment.

Bought movie tickets but don’t really want to go anymore? Option, not obligation.

Purchased a pair of shoes but don’t really like them? Don’t wear them because you feel obligated to, that money’s gone. You only have the option to wear them.

Been friends with someone for 5 years and they’re turning into a miserable drain on your energy? You have the option to continue that relationship, but not the obligation.

As you get in the habit of identifying when you feel obligated, it will become easier to weed those impulses out and do what you truly want. As you do, you’ll start using your time, money, and emotional energy significantly better, no longer being swayed by past choices, and being less tempted to overinvest in past decisions.