Forget Commitment: Invest in Something

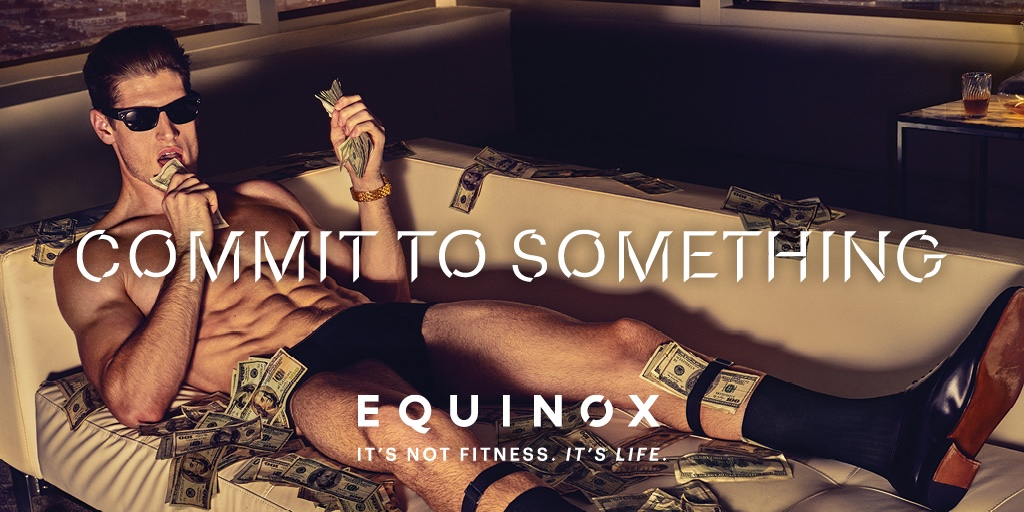

As a New York tech yuppie, I’m obligated to work out at Equinox.

When you enter an Equinox, you’re greeted by their current advertising campaign: Commit to Something.

It’s a sexy, alluring, call to action to combat what’s most likely their biggest source of customer churn: people quitting. Most people who don’t frequently exercise dread it. They see it as something they should do. Something they’re supposed to do. Not something they want to do.

Sticking with exercising regularly is hard. People want fast results. They want to go in for a few weeks and suddenly be in great shape. To do a one week juice cleanse and look like that Instagram model they’re following. And when that doesn’t happen, they tend to give up and go back to eating cheetos on the couch.

In that sense, Equinox’s campaign is clever. It suggests people should commit to, well, something. And if you commit to something, you’ll end up looking like their scantily clad model swimming in Benjamins. But the phrasing doesn’t feel quite right. Commitment may not be the best way to motivate people.

Hot Girls Wanted

Netflix’s “Hot Girls Wanted: Turned On” docuseries explores sexuality in modern society.

In episode 2, we meet James, a 40-year old former reality TV star and serial-dater who churns through sexual partners as fast as he can swipe them.

The episode opens with him meeting a woman he develops a genuine connection with. They go on multiple dates. They’re having a great time. They make out in the parking lot after dinner. He’s telling the audience how into her he is.

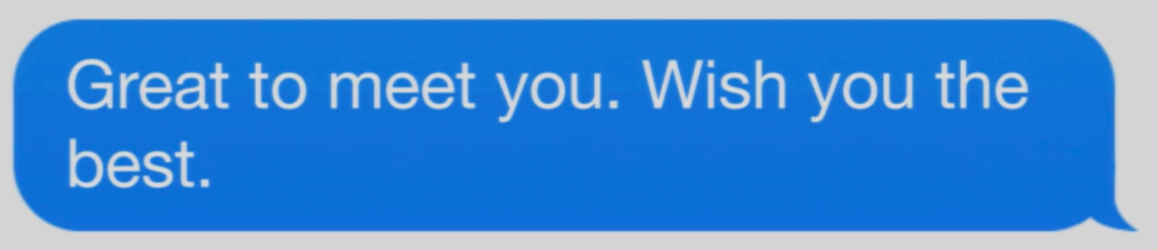

Then… the fall. He sends her a drunk text from a BBQ. She gives him a hard time for being drunk on a Monday as a 40-year-old. He says that he’s sorry she feels like there’s something wrong with having fun at his age. She apologizes and tries to explain that she didn’t mean to insult him, but in response, he simply tells her:

After seeing how well their relationship developed over the past 30 minutes, it’s easy to cringe at how fast he tossed her away. But we all know someone like this, don’t we?

The friend who keeps tossing away dates because they aren’t perfect. The one who wants a relationship that’s only exciting, and requires no work. Who wants someone that already completely satisfies them. And who is so impatient that the minute they run into a small bump in the relationship they toss it aside and pop open Tinder to try again.

When the next person is a swipe away, they feel there’s little reason to keep pursuing any relationship with a flaw.

There are plenty of other options, so why commit?

The Undefined Decade

James is living a millennial sexual fantasy, but the consequence is the mortal terror that tends to grab people, particularly women, in their early 30s, as Meg Jay described in The Defining Decade.

According to Dr. Jay, many of her therapy patients are 30-year-olds who regret not finding and developing a relationship in their 20s. They now feel like they’re scrambling to find someone to marry and have kids with, and that scramble heightens the normal amount of relationship anxiety while also naturally leading to finding a less than ideal partner.

As one of her patients put it:

“Dating for me in my twenties was like this musical-chairs thing. Everybody was running around and having fun. Then I hit thirty and it was like the music stopped and everybody started sitting down. I didn’t want to be the only one left without a chair. Sometimes I think I married my husband just because he was the closest chair to me at thirty. Sometimes I think I should have just waited for someone who might be a better partner, and maybe I should have, but that seemed risky. What I really wish I’d done is thought more about marriage sooner. Like when I was in my twenties.”

Across the board, her patients regret putting off this part of their lives until later. They didn’t commit to a relationship earlier, and now they don’t have as much time to fully develop one before their biological clocks run out.

James, Jay’s patients, and other millennials foregoing commitment in pursuit of the perfect relationship are committing what I’ll call the “maximization fallacy.”

Maximization fallacy : The belief that you’ll be happier trying to find something perfect, than something good enough that you can improve on.

The fallacy is based on Herb Simon’s work on “satisficing.” Essentially, in situations where the ideal choice is unclear, we tend to pick the “good enough” option. It’s a way for our not-so-rational brains to make decisions in a world where they could otherwise spend an infinite amount of time calculating perfect preferences. It’s why people who lose their emotional cores can’t make decisions. Pure logic machines can’t satisfice.

Someone is a satisficer if they can default to the good enough option. They’re a maximizer if they need the best option. Which camp you fall into will vary depending on how much you care about the area you’re making decisions in, but we also tend to be more macro-satisficers or macro-maximizers.

If you truly tried to maximize everything, you’d never make any decisions and be a neurotic mess. If you were a perfect satisficer, your decisions would be instant. Most of us are somewhere along the satisficing – maximizing spectrum.

One of the biggest influences on how much we tend towards maximization is the availability of options. The more options we believe we have, and the more rapidly we think our options are changing, the more we’ll tend towards maximization.

If you grew up in a small town in North Dakota with a dozen suitable mates your age, and no intentions of leaving the lovely (and very flat) Billings County, you’d feel perfectly comfortable getting married in your early 20s.

But when the average Tinder user swipes through 160 profiles a day, the options, and potential for maximization, are endless. It becomes easier and easier to get in the mindset that you don’t need to satisfice because you have near infinite options to maximize around.

But when you will only accept perfection, you either never choose something, or you pick something and dispense with it as soon as it feels like you might find something better.

With relationships, that doesn’t go so well, as James and Jay showed us. Relationships are just one example, though.

Attention Deficit Entrepreneur Disorder

If you hang out with entrepreneurial or wantrepreneurial types, then you may know someone with Attention Deficit Entrepreneur Disorder.

It’s exactly what it sounds like. An entrepreneurial person who can’t focus on one project, or even one set of projects. Who keeps spinning up new ideas, buying new domain names, talking to their friends about the next big idea they’ve come up with.

They always have good reasons for their indecision, of course. They’ll say the idea wasn’t actually that good. The market wasn’t ready. They didn’t have enough money. People didn’t get it. They found a better use for the technology. They pivoted.

They jump between businesses the same way James jumps between relationships. But both behaviors are symptoms of the same problems. Maximizing over satisficing. Refusing to commit to something.

The Fetishization of Options

There’s a popular piece of advice that you should optimize for options. I believe I first heard it from Derek Sivers, who restated this idea in his article on how to thrive in an unknowable future:

“Choose the plan with the most options. The best plan is the one that lets you change your plans. (Example: renting a house is buying the option to move at any time without losing money in a changing market.)”

It’s an attractive sentiment that plays to our desire not to commit to anything. But it’s flawed. It’s useful in certain cases, say, deciding what to study during college, but it breaks down for anything that requires an ongoing investment.

Part of the problem with option optimization is it makes us unhappy. In “The Paradox of Choice,” Schwartz provides a few simple rules for managing choice overload. One of those rules is to make non-reversible decisions:

“Don’t worry about opportunity cost too much. Stick to things you always buy, avoid “new and improved,” don’t scratch unless there’s an itch, and remember that you can never take advantage of every single opportunity in the world so stop trying to find all of them… Make your decisions non-reversible.”

Why should we make non-reversible decisions? Because if we don’t, we engage in “Counterfactual Thinking,” a term popularized by Kahneman and Tversky that describes our tendency to imagine different histories and futures in our heads, envisioning all the things that could have gone, or could go, differently, if something else had happened in the past.

In Godel Escher Bach, this is introduced as a television set where you can “tune” the dials to see different potential histories and futures of a football game. Tortoise, Crab, Sloth, and Achilles keep tweaking their “Subjunc-TV” to imagine different ways the game could have gone to avoid a key player fumbling, and they end up introducing so many counterfactuals the game eventually morphs into four-dimensional baseball.

That’s what we’re all doing in our heads all the time. Tuning the dials on what happened in the past, to imagine a different present or future for ourselves. The more options we give ourselves, the more dials we have to play with, and the more utopian futures we can imagine.

Neil Soni refers to this as the “Optionality Trap,” drawing from an article in the Harvard Crimson by Mihir Desai. As Desai puts it:

“By emphasizing optionality, these students ignore the most important life lesson from finance: the pursuit of alpha. Alpha is the macho finance shorthand for an exemplary life. It is the excess return earned beyond the return required given risks assumed. It is finance nirvana.

But what do we know about alpha? In short, it is very hard to attain in a sustainable way and the only path to alpha is hard work and a disciplined dedication to a core set of beliefs. Given the ambiguity over the correct risk-adjusted benchmark, one never even knows if one has attained alpha. It is the golden ring just beyond your reach—and, one must enjoy the pursuit of alpha, given its fleeting and distant nature. Ultimately, finding a pursuit that can sustain that illusion of alpha is all we can ask for in a life’s work.”

The reference to finance is apt because to understand the perils of optionality and constant track switching, we’ll need to take a quick detour through crypto trading.

HODL

If the cryptocurrency community has a unifying philosophy, it’s “HODL.” A conceptual meme suggesting that the right move is to hold onto your crypto investments, not to sell. No matter how bad the dip gets.

Despite the recent crash, there’s a certain wisdom to this philosophy. People are irrational maximizers who want to make money NOW, and frequently make the mistake of selling low and buying high. But if you commit to the philosophy of HODL, you surrender your freedom (options) to sell at the dip, and hopefully, make money over time.

Part of why this strategy works is trading costs. Even if you could accurately predict the market, there’s a cost to constantly changing your position. If you buy and sell your bitcoin through Coinbase, you have to give up 2-3% of the trade amount on each transaction.

If two people had 1 bitcoin at the beginning of the month, and one person HODL’d while the other sold it and re-bought it each day, the first person would end up with much more value simply by not paying the trading costs. If the price didn’t move at all, and we assume a 2% transaction cost, the first person would still have 1 bitcoin while the second would be down to .54btc.

By ignoring options and staying the course, HODLing pays off.

Productivity

A more familiar example of these costs can be found in productivity.

Multitasking is (mostly) a myth. When we think we’re multitasking, we’re really just doing rapid task switching: bouncing around between multiple focuses, not really doing them at the same time.

The problem with multitasking is that each time you switch what you’re focusing on, you pay a price in terms of rate of output. It takes a few minutes to get back up to your peak productive speed, so each time you switch what you’re focusing on, you lose that time again.

If you’re familiar with the concept of flow from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work, you know that it’s impossible to sustain flow on anything if you’re being constantly interrupted. If flow is the peak productive state, which it seems to be, then reaching peak productivity is largely a function of ignoring all of the options you have for other things you could be working on.

This works on the micro scale, applied to the task at hand, but we can also draw it out to the macro:

Just as constant task switching erodes your short-term productivity, constantly changing your big picture focus will destroy your long-term productivity.

But macro-task switching doesn’t incur the same sense of lost productivity that micro-task switching does. While we can feel the bump in the productive road that comes from checking Twitter, it’s harder to notice these switching costs when they’re not obvious. When they’re affecting our long-term productivity instead of our short-term productivity.

The switching costs for our bitcoin position are clear. You can see them on your Coinbase receipt. But what’s the switching cost for a business venture? For a relationship? For a workout routine? These investments don’t provide nifty receipts of what you’re sacrificing by changing your mind, and as a result, we discount the cost to zero.

Switching costs are only part of the problem, though.

Buy High and Sell Low

The opposite of HODL is “buy high and sell low.” Instead of sticking with your investments, you get freaked out and sell when they dip, and get exuberantly stupid and buy when they peak. It’s a perfect analogy for what we do in the other areas of our lives where we fail to sufficiently commit.

First, we buy high: latching on to something that’s exciting now. The latest Tinder match. The newest idea. The sexiest diet. And then we ride it for as long as the excitement lasts.

When it gets difficult, boring, or something sexier comes along, we quit (sell low).

To put it another way, we ride new things out till they hit The Dip, then abandon ship for the next thing that hasn’t hit its dip yet. The next honeymoon phase. The next exciting domain purchase. The new thing we’re going to be better than 80% of other people at.

But as anyone who’s stuck with something for long enough knows, that dip is a necessary phase in the progression of whatever you’re doing. A relationship needs to move out of the honeymoon phase and start having some real disagreements to grow. A business needs to have some scary, difficult periods to create a moat that other businesses won’t easily cross. A fitness regime, or diet, will naturally get boring and frustrating at some point.

And here’s the thing: you (and I) likely agree with that paragraph, but we completely ignore how the need to traverse the dip applies to certain domains. I completely understood the need to stick it out through a boring weight lifting plateau, but it took a year and a half of nomadic travel to realize that applied to cities as well.

Growing the Machine

This was made particularly obvious to me with the initial months of growing Growth Machine. I was bringing on clients quickly, and hitting the limits of my capacity. I soon had to decide whether I wanted to keep it smaller, with me as the only real employee, or bring on other full-time team members.

Bringing on full-time people is scary. It’s a commitment. It makes it harder to quit if you get bored, and it starts incurring real costs where you have to maintain a certain amount of revenue to keep everyone on the team employed.

But it’s also a necessary investment to grow the business. It’s nice to have the freedom to quit, speed up, slow down, whenever you want, but that optionality has a cost. If you try to hold on to that freedom, the business can never grow.

You have to invest to grow, and investment means giving up other options.

It means trading freedom for the potential for growth.

Invest In Something

And this is where Equinox gets it wrong. Commitment is a bad word. It suggests fighting yourself to act against your impulses. It suggests doing something “because you should.”

That’s not motivating, though, and focusing on commitment runs up against the maximization impulses we know we have. Instead, forget commitment. Think about what you want to invest in.

You’re not committing to working out, you’re investing in your health, whether that means looking good at the beach or being able to run around with your grandkids.

You’re not picking one idea to commit to working, you’re choosing which one to invest a serious chunk of your time in.

You’re not committing to someone, you’re choosing who you want to invest in developing a relationship with.

A meaningless semantic difference? Perhaps. But I find the distinction useful. Investment requires thinking seriously about where your resources should be allocated, having criteria for de-allocating them, and then sticking with your investment until those quitting criteria are met.

And this is where we get to the core difference. Why investment is so important.

Investment and foregoing options is necessary for any growth.

If you want a relationship to grow, you can’t keep the freedom to date anyone you want.

If you want a business to grow, you have to sacrifice the freedom to work on anything you want.

If you want a (financial) investment to grow, you have to surrender the freedom to use that money for whatever you want.

Don’t commit to something. Invest in something.