Cultivating High-Quality Inputs for High-Quality Outputs

“If you don’t pay appropriate attention to what has your attention, it will take more of your attention than it deserves.” — David Allen”

In The Sovereign Individual , authors James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg argued that as we transitioned to the Information Age, we’d move from nation states and large societies to a world of radical personal and financial freedom.

As they described the world of tomorrow, they argued that everything traditionally “broad-casted” would become “narrow-casted.” Instead of broadcast news where everyone gets the same information, we’d each have our own narrow-casted information stream:

“As individuals themselves begin to serve as their own news editors, selecting what topics and news stories are of interest, it is far less likely that they will choose to indoctrinate themselves in the urgencies of sacrifice for the nation-state.”

They presented it as a utopian ideal: we’d wake up each day to a curated feed of the news most important to us before embarking on our day. But the world we’ve gotten is a bit different.

While Rees-Mogg and Davidson imagined that a free market for information would aid self-education in the same way a free market benefits economies, a nasty side effect has come with it. We each have the ability to learn, study, read, or watch almost anything in the world, but we have to wade through a growing sea of garbage to get to it.

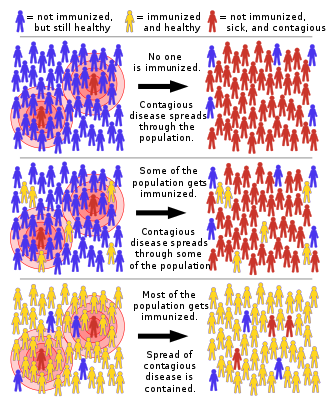

We may not have had as much access to information before the internet, but we at least had some herd immunity from bad information. When there were stronger gatekeepers, it was harder to publish junk. But now that the gatekeepers are gone, someone like Alex Jones can reach more people in a day than Lincoln reached in his lifetime.

Herd Immunity visualization from Wikipedia

Ten years ago, we used the Internet primarily to answer questions. We went into it looking for information. Today, we allow it to push information onto us, a problematic switch I’ve discussed at length. With that switch, we have allowed other people to choose where our attention goes. The most clickable ad, the most addictive game, the juiciest headline: they all hijack our attention from what we want to direct it towards to where they want us to click and spend time.

In the attention economy, if you don’t control your attention, someone else will gladly do it for you.

As a result, most of us are living a life of low-quality inputs, dictated by the newsfeed, what’s trending, what’s on the news, what ads throw at us, what just hit the bestseller list, or what has been well marketed.

Which is why we have to make an effort to design a life of****high-quality inputs. One where we’re being deliberate in what we consume in order to live happier, higher output, and more effective lives. Where we’re choosing and pulling what we want to learn or be entertained by, instead of having it pushed onto us.

This is the third article in my series on designing a high-output life. If you haven’t read the other articles,__I recommend getting them here .

Defining Low-Quality Inputs

A low-quality input is any source of information that does some combination of:

- Push entertaining information onto you to keep you engaged

- Distract you with meaningless information made to feel meaningful

- Decrease the quality of its information in order to force you to return

Facebook is the simplest example of the first: they invest their time, money, and energy in controlling what you see on the Internet. Their goal is to get you to spend more time on Facebook and click on more ads. Not to make you happier, more well informed, or more well connected.

The news is a strong example of the second: by giving what Neil Postman calls a “pseudo-context” to meaningless information, it makes you think some flood across the world is relevant to your life right now. It tells you plenty about what is happening somewhere, but not anything about that area. Many Americans knew about the war in Iraq, but how many knew anything about Iraq?

The third bucket for low-quality inputs are the ones that decrease their information quality in order to force you to return: typically, magazines or blogs that are ad-financed. Men’s Health can’t give you a complete health solution in one article. If they did, you’d stop reading Men’s Health! So instead, they write useless listicle tip articles to keep you sucking at the teat of information while they show you ads for growing back your hair. Information degradation via artificial complexity.

It’s worth mentioning here that purely entertaining information is not necessarily low quality. Puppy videos are a great use of time to relax and feel good. But if you spend all day scrolling through Facebook because it’s using intermittent puppy videos to get you hooked, then you have a problem.

The core issue is the incentives of the source of whatever information you’re consuming. Facebook, Twitter, Magazines, News, they all make money from ads which means they need as much attention as possible.

A book, by contrast, has already sold you and doesn’t need to keep you coming back. It only needs to deliver on its promised value so that you buy the next book from the author. Similarly, reading apps like Instapaper are popular because they create a great reading experience, so they’re not incentivized to interrupt you or blast you with ads.

An easy response here is to ask: so what. If you like watching the news, hanging out on Facebook, reading health magazines, what’s so bad about that really? And to be fair, nothing is truly bad , just problematic, especially for building a high-output life.

The Problems with Low-Quality Inputs

The most obvious issue with low-quality inputs is the opportunity cost. Any time you’re putting towards a low-quality input is the time that you’re not putting towards creation, high-quality inputs, or fun.

This has, by far, been the biggest boon to shutting off my Facebook newsfeed and turning off phone notifications. I have so much more time for other inputs. By getting 30-60 minutes of my day back I can fly through articles and books that give me better, higher quality information.

Quality of the actual information is important, too, since low-quality inputs have a bad habit of teaching you things that are simply false or only half true. Facebook still has a problem with fake news spreading, and it makes sense. From Jonah Berger’s work in Contagious, we know that what gets clicks are things that outrage, amaze, or terrify us. And the best way to make something more terrifying, amazing, or outraging is to tweak it, or flat out lie, so it gets clicked on.

News outlets are guilty of this too. Huffington Post, among many others, will turn extremely questionable “research” into videos that will make people feel good about themselves and share it. It’s not about informing you—it’s about getting ad impressions.

That’s why part of our cultivation of high-quality inputs has to involve finding sources on the Internet we can trust. Reputation for information quality is everything now , and if it turns out that something or someone you’re following is twisting the facts and not correcting course when they’re made aware of it, they have to be purged.

We also run the risk of developing Crony Beliefs if we don’t carefully cultivate our inputs. I (along with everyone in the tech world) thought that the Net Neutrality bill repeal was a bad thing.

Then I read this article by Stratechery. The article gives a great explanation of why this repeal is not a big concern, but if I hadn’t gotten a different viewpoint then it would have been easy to follow along with the beliefs of my in-group and never get a full perspective. We all do this all the time, and will always continue to do it, but by seeking out high-quality inputs from a variety of views we can get a slightly wider perspective.

Which brings us to the most important question: in a world that wants to distract us and suck up our time with low-quality information, how do we redesign our life to focus on high-quality inputs without becoming a hermit in the woods?

How to Cultivate a Life of High-Quality Inputs

In Deep Work, Cal Newport lays out his argument for why the successful people of the future will need to learn to focus intensely for long periods of time in order to accomplish their best work. It’s a useful read, and within it, he makes an argument for how to treat your sources of information that he calls the “Craftsman Approach to Tool Selection”:

“The Craftsman Approach to Tool Selection : Identify the core factors that determine success and happiness in your professional and personal life. Adopt a tool only if its positive impacts on these factors substantially outweigh its negative impacts.”

Instead of trying to use every tool available, or what tool is popular right now, or what tool your friends are using, find the tool that’s the best for the job you’re trying to do. If you’re trying to learn something, read a book. If you’re trying to have fun, go do something fun. If you’re trying to find out how your friend is doing, call them.

A simple heuristic for information is that it should answer a question you have, solve a problem you’re facing, or simply be likely to make you think in a way you haven’t before. If it’s not doing one of those things, then it’s either not useful or at least not useful right now and can be filed for later.

Newport’s Deep Work view of the world is a tad idealistic: we can’t always shut ourselves off for hours at a time and silence the noise of the Internet. And quitting the information stream of the Internet isn’t necessarily valuable. Instead, we have to become more informed consumers of information. We have to learn how to discern what’s high quality, what’s low quality, and make our best efforts to keep out the low-quality sources.

It’s similar to our relationship with food. For most of human history, food was scarce, so we evolved to eat whatever we had available to us. Now, food is abundant, and that tendency is making us fat. Information, too, used to be scarce , and usually related to us not dying. Unless we want to become info-obese, unable to resist the tasty clickbait in front of us, we’ll need to fight our evolutionary tendencies.

In his article “The Acceleration of Addictiveness,” Paul Graham pointed out how technologies seem to be getting more addictive over time. Facebook is more addictive than TV which was more addictive than radio which was more addictive than the newspaper. If he’s right about addictiveness accelerating, then we’ll have to be particularly careful how we treat any new information technology.

Similar to how being in good physical shape is now not the norm in western countries, a reasonable relationship with information may make you seem like a Luddite. Or as Graham put it in the article:

_“Already someone trying to live well would seem eccentrically abstemious in most of the US. That phenomenon is only going to become more pronounced.You can probably take it as a rule of thumb from now on that if people don’t think you’re weird, you’re living badly.” _(emphasis mine)

Cultivating a life of high-quality inputs at this point means behaving in ways that seem strange. It means not using ephemeral media channels like Snapchat, and disabling most of Facebook. It means ignoring the news, and advertising, as much as possible. It means skipping the bestsellers lists, magazines, and pop-info blogs. It means rethinking your Internet used to be focused on finding valuable information, instead of being passively entertained.

It also means looking for lists of books you trust instead of going with the bestseller lists (to start, you can check out mine, Taylor Pearson’s, or James Clear’s). It means following blogs that you like using Feedly (instead of email) and reading them in Instapaper. It means paying for good online material instead of trying to get everything for free and paying to remove ads whenever you can.

And most importantly, it means creating a narrowcast that serves you. Becoming a healthy, intelligent consumer of the vast information we have available to us, in the way Rees-Mogg and Davidson envisioned.