Unqualified Experts: 5 Rules for When to Ignore Authority

I’ve resisted sharing this for a while. It makes me laugh when I think about it, and it’s a valuable lesson, but there’s no way to talk about it without burning a few bridges… so between us, if you know anyone I mention in the coming paragraphs, don’t tell them. It’s our little secret.

For background, between October 2013 and 2014, I ran a startup called Tailored Fit where we were designing technology to provide algorithmic clothing recommendations. Think Pandora + shopping. It ended up crashing and burning in wonderful fashion (pun intended), but that’s not the story here.

This story begins with John (all of the names and companies in this article are pseudonyms).

Tailored Fit began at a Startup Weekend, a fun event where people who don’t really know what they’re doing (but who have excellent energy) get together to start a company in 3 days.

Yeah, startups!

You pitch ideas, join a team, chug RedBull, maybe order a keg, and see how far you can get on your product and business over the weekend, before pitching to a panel of judges at the end.

The second day of the event, I was approached by one of the organizers:

“Hey Nat, you’re doing a clothing related startup, right? The former CEO of Acme Retail (the real company is one you know) is pretty active in the startup scene. His name’s John, you should reach out to him, here’s his email and phone number.”

“… I can just call him?”

“Yeah, tell him it’s about startup weekend and he’ll talk to you.”

Star-struck that I was getting to talk to someone who had been so high up in the retail industry, I tapped John’s number into my phone and started pacing back and forth at the bottom of the stairwell.

John was incredibly gracious with his time. I asked him everything I could about the industry, he gave me his thoughts on what we were working on, and I ended the call an hour and a half later invigorated with newfound validation.

We won Startup Weekend and were accepted into a local startup incubator where John was one of the mentors. The job of a mentor is to give advice to companies, help them grow, make introductions, etc. I could hardly talk to anyone about what we were working on without them asking “Have you met John? He used to be the CEO of Acme…”

Fast forward a few months. It’s March 2014, we’re halfway through the incubator program, and I’ve decided to spend a weekend half-drunk starting a gag company as a parody of the silly things people do at Startup Weekend (including myself).

Slightly less serious this time

Partway through the weekend, an incubator alumnus Ben and I are talking, and he drops this on me:

“Want a bit of a head-trip? Go through John’s LinkedIn and tell me what’s missing.”

“Huh?”

“He was never CEO of Acme, there’s no record of it there or in Acme’s history.”

“That… can’t be right.”

I went home that night and scoured through everything I could find online about Acme, as well as John’s LinkedIn, and there was no record of John as CEO anywhere.

Now this wasn’t a crazy mistake: he’d worked as other C-Suite and President positions, and certainly had the credentials to talk about the industry, but he’d never been CEO as far as I could find. And then I realized, he never said he was, that was all from other people.

It seemed crazy that idea could survive for so long, but nevertheless, it had. I had been told it over and over again by people who never checked its validity, and I was repeating it to others as well!

And while that was a little mind-boggling, there was a much more interesting question: “who else isn’t as much of an authority as they’re regarded to be?”

The answer, it turned out, was just about everyone.

Authority Schmauthority

As I dug in on many of the people we were listening to, I kept finding cracks in the authority they were giving advice from. John ended up being one of the mildest cases!

Just because someone was in an angel investor group didn’t mean they made investments. Working for the university entrepreneurship department didn’t mean they had impressive entrepreneurial accomplishments. Being a mentor for the accelerator didn’t mean they had relevant startup experience.

One investor, Brian, had introduced himself to us as having started a company, grown it using Lean Startup principles, and then eventually had it acquired by Zip3 (again, big company you’d recognize).

My initial reaction was “oh whoa, that’s impressive!” Until I dug in and realized it was acquired for $500,000 after 4 years of work and having raised $1,500,000.

If he had said that up front, he could have given advice from the standpoint of “hey this didn’t go well, here’s what I learned and the lessons you can take from it.” But by pretending it was a big success and demanding respect for it, that authority disappeared the moment the veil was lifted.

People kept falling into one of three categories:

- They had oversold their expertise

- Other people had oversold their expertise

- Their position implicitly oversold their expertise

The Tipping Point

I slowly realized that almost everyone who had been praising me for the last 6 months and telling me how well the company was doing had no idea what that even meant. Most had never run a successful tech startup. Actually, none of them had, depending on where you draw the “successful” line.

And when I realized that I shouldn’t be taking advice or heeding praise from people who didn’t really know what they were doing, a second, more painful realization followed: I had no idea what I was doing.

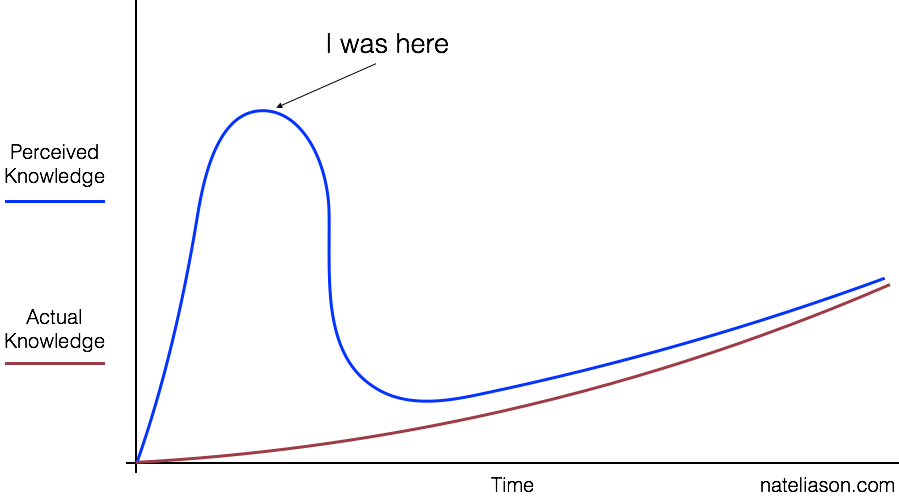

And so began the painful ride down the cliff of perceived knowledge

All of my assumptions that I was doing the right thing and had this startup stuff figured out were based on positive reinforcement from people I’d now realized weren’t necessarily qualified to give it.

Over the next couple months, I realized the company was going nowhere, folded it, and left the community, trying to get out of the environment as quickly as possible.

5 Rules for Advice from Authority or Experts

Since then, multiple entrepreneurs in that scene have asked me some form of the questions: “does X know what they’re talking about?” “Do you think I should take X’s advice on Y?” or “Who should I ask about Z?”

My response is usually some form of the following rules, with the warning that if they follow my advice, they must also question any advice I’m giving, a contradictory tip usually followed by confused looks and tilted heads.

Why am I giving advice in this post then? I mention it in point 2, but I don’t expect you to take anything I say on blind authority. Whenever possible, I try to speak from the experience of something I went through or realized and the extent to which you implement that yourself is 100% up to you.

Rule 1: Decide For Yourself if They’re an Expert

Just because someone has some job, title, or was referred to you by someone else you respect doesn’t mean that they’re experts and worth listening to. Someone with money to invest isn’t necessarily a skilled entrepreneur, a professor of entrepreneurship isn’t necessarily a good startup advisor.

You have to dig into their history and their experience as much as you can and judge for yourself if they’re someone worth taking advice from. Ignore things they’ve said about themselves as much as you can; it’s natural to slant anything about ourselves to be as positive as possible.

Rule 2: Check if They’re Speaking from Experience

Ideally, someone will only give you advice based on personal experience, and from experience that is relevant to your situation and proves their expertise.

The best way to test this is to ask for stories. Don’t let someone give you lofty advice. Ask them for a similar situation that they were in and how they handled it. If they can’t give one, that’s a sign that the advice they’re going to give you won’t be worth listening to, and a strong sign that the authority and expertise they’re giving advice from is suspect.

Rule 3: Check if Their Experience is Relevant

The challenge with trying to emulate others’ accomplishments is the narrative fallacy that comes with it. People will succeed for all sorts of reasons, and it’s your job to figure out if their success was a result of tactical decisions that you can follow, or if they got lucky and made up a story after the fact.

To test this, ask yourself if you could feasibly replicate it, or if their success was determined by some lucky break. Luck will always come into success to some extent, but if it accounted for more than ~20% of their success in the instance they’re drawing advice from, then you have to throw it out.

But you don’t have to throw everything out, just the pieces that are clearly luck based. It’s up to you to decide what’s repeatable and what isn’t, and then mold it to your advantage.

Rule 4: Ask if You Want to Be Them, or Achieve the Same Level

You also have to ask yourself if the expert is somewhere you want to be. Their advice won’t necessarily help you reach your goals, it will help you reach their level.

If a homeless person stumbled up to you and started giving you advice to short the NASDAQ and capitalize on the (assumed) growing tech bubble, you’d be suspicious. They’re not in a place you want to be financially so why would you take their financial advice?

If someone’s claim to fame is a few failed companies and one aqui-hire, you probably shouldn’t take startup advice from them. If an overweight and unreasonably loud (probably white) middle aged guy in a tracksuit is giving you diet and exercise advice, politely ignore it and jog half a mile away to where you’re out of earshot.

Rule 5: Recognize Domain-Specific Expertise

You might have a friend who’s a skilled statistician, but that doesn’t mean that they will give you good dietary advice.

Now obviously, you wouldn’t make that mistake (I hope!), but there are less obvious ones: the professional mentor who gives relationship advice, the parent who gives diet advice, the runner who gives medical advice, the big-company CEO who gives founder advice, the medical devices expert talking about shopping startups.

It’s these close associations that you have to be careful about. When someone’s expertise is near to the thing they’re giving advice on, we forget to question it as carefully, and can end up taking bad advice in the process.

Be Nice About It

Now all of that said, don’t be a dick when you realize someone is full of it. It won’t help you to throw it back in their face, since, in most cases, they’re trying to be helpful and think they’re doing a good thing.

They aren’t bad people, frauds, etc. they just haven’t earned the right to give you advice, and you need to realize when to filter it out.